Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI), also known as ‘brittle bone disease’, is a complex genetic disorder characterized by fragile bones that break easily, alongside other manifestations affecting various body systems. The range of symptoms can vary widely from person to person, with the disease spectrum extending from mild cases to severe, life-threatening conditions. This diversity makes OI a challenging condition to diagnose and manage.

Joint hypermobility

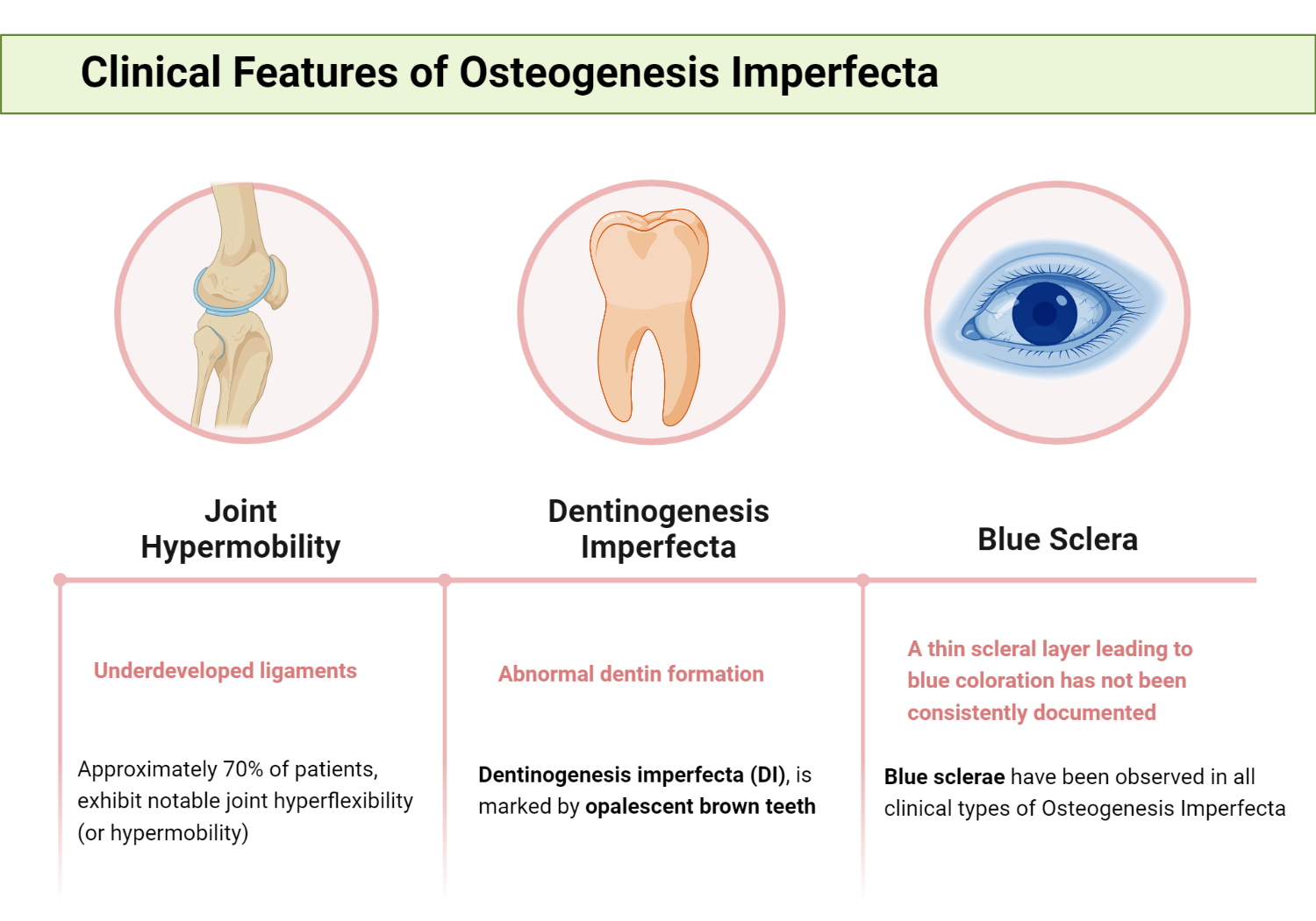

A significant proportion of patients with OI, about 70%, exhibit notable joint hyperflexibility (or hypermobility) due to underdeveloped ligaments, a common characteristic of this condition. This feature is more prevalent in patients with more severe forms of OI. Joint flexibility is more apparent in younger patients and generally affects smaller distal joints as opposed to larger proximal ones, which are typically affected in conditions such as Marfan syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS)

Infants with OI may seem to have loose joints and a somewhat floppy physical constitution. Although sprains and dislocations are not common, with enough stress, problematic dislocations can occur at the hip, knee, ankle, or shoulders. In more severely affected patients, muscle tone tends to be poor, either due to lack of use or due to underlying abnormalities in connective tissue within the tendons. Furthermore, flat feet are a common condition seen in patients with OI.

Skin Changes in OI

The reduced thickness in OI patients is likely the result of diminished collagen production. The skin’s ability to withstand tension is reduced where type I collagen production is impaired. While skin laxity is usually mild, it is considerably less than the hyperelasticity typical of EDS. Unlike the fragility of the skin in EDS, wound healing in OI is generally normal.

A specific skin lesion, similar to those found in other connective tissue disorders such as EDS and pseudoxanthoma elasticum, has been reported in OI This lesion starts as a keratotic papule and grows into a winding macule, which typically appears on the arms or trunk. Patients with OI may form thin, wide scars, and on rare occasions keloids may be found.

Dentinogenesis Imperfecta

Dentin, the organic structure of teeth, is made up of type I collagen and proteoglycans. Dentinogenesis imperfecta (DI), marked by opalescent brown teeth, arises from inadequate support for the overlying normal enamel. With the ongoing strain of eating, this enamel can fracture, revealing the dentin below, and the tooth might wear down to the gum level.

Dentin, which shares the same type I genetic collagen as bone, exhibits increased amounts of hydroxylysine compared to lysine in patients without noticeable DI. This coincides with the overmodified collagen molecule found in connective tissues in severe OI. As seen by scanning electron microscopy, the dentin displays an irregular tubular structure contrasting the highly organized tubular pattern found in normal dentin.

Radiographic features of DI include normal enamel density and thickness, accentuated constriction at the junction between crown and roots, and pulp chambers that may initially be larger than normal but eventually become filled by abnormal dentin.

Approximately a quarter of each clinical phenotype is also found to have DI. Interestingly, DI has been found to be somewhat rare in patients with mild disease and more frequent in those with severe bone disease.

Genetic evaluation of families with dominantly inherited OI has shown that when DI is present in a family, all affected individuals will have both skeletal and dental disease. However, there is no correlation between the severity of skeletal disease and the presence of DI in affected families. Also, rarely, families have been reported to have DI and blue sclerae, but not bone disease.

Genetic research on inherited OI has shown that in families where DI is present, all affected members will have both bone and dental anomalies. However, there is no correlation between the severity of bone disease and the occurrence of DI in those families. In rare cases, some families have been reported to have DI and blue sclerae without any associated bone disease.

Blue Sclera in Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Blue sclera, a notable clinical characteristic of Osteogenesis Imperfecta, has been observed since initial descriptions in the 1830s. Type I collagen is present in various parts of the eye, including the cornea, sclera, choroid, iris, and ciliary body. Despite common belief, a thin scleral layer leading to blue coloration has not been consistently documented. Studies have indicated a shortage of scleral collagen and an elevated presence of a stain indicating an increase in the mucoid component of the sclera in patients with this clinical manifestation.

Blue sclerae have been observed in all clinical types of OI. In some instances, the blue color tends to lighten with age, whereas in severe cases of bone disease, white sclerae are commonly seen. It is important to note that blue sclerae are not exclusive to any one OI subtype and therefore should not be used as a defining characteristic of clinical subgroups. This blue hue in the sclerae can also be seen in other inheritable connective tissue disorders and in some individuals without any disease.

In terms of other ocular abnormalities, studies have reported a variety of conditions in a small number of patients with blue sclerae, such as keratoconus, corneal perforations, and megalocornea. The most commonly observed condition is arcus juvenilis or senilis, which can be seen even in the absence of blue sclerae. Interestingly, myopia, often observed in other connective tissue disorders, is not typically associated with OI.

Ear changes in Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI) presents with various otological and maxillofacial features. Approximately 10% of patients with OI require the use of a hearing aid due to functional deafness, which usually presents during the second or third decade of life. Furthermore, subtle defects in auditory function are observed in nearly 90% of older individuals. The exact nature of these defects and the functional disturbances that cause progressive hearing loss in some patients have not been fully elucidated at this time.

Historically, the anatomical defect in OI was thought to be identical to otosclerosis; now, they are recognized as distinct conditions. Notable biochemical differences have been identified in the ossicle bones of patients with OI and otosclerosis. Furthermore, unlike otosclerosis, OI patients present with a diminished skeletal bone mineral content. Also, the histopathological condition of the temporal bone in patients is similar to that of the peripheral skeleton, presenting deficient ossification.

Deficiency in ossification affects the tympanic ring, ossicles, cochlea, and otic capsule, and intracochlear hemorrhage can also occur. Microfractures are observed in the incus and stapes, and the stapes may eventually degrade to thin fibrous threads. Interestingly, the stapes footplate may be embedded in vascular fibrous tissue, which has led to its association with otosclerosis.

A distinct audiological pattern is typically observed, consisting of a high-frequency sensorineural loss that intensifies at higher frequencies. As patients age, hearing loss extends to lower frequencies. It is also worth noting that another otologic feature of OI is increased compliance of the tympanic membrane, indicative of excessive mobility or discontinuity of the components of the middle ear.

Cardiac changes

The myocardium has an extensive network of collagen, and also, cardiac valves consist mainly of collagen. Different types of collagen, specifically types I, III, and V, are prevalent in these structures, with types III and V particularly found in the vascular components of the heart muscle, valves, and supporting fibers around muscle cells.

Various heart conditions have been reported in patients with OI, including mitral valve prolapse, aneurysms, and dissection of the aortic root or cervical vessels, as well as Ebstein’s anomaly. Nevertheless, these are considerably less frequent than in conditions such as Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS) or Marfan syndrome. These cardiac lesions are rarely clinically significant and do not appear to be associated with the severity of skeletal disease or the presence of blue sclerae.

Short Stature in Osteogenesis Imperfecta

Reduced skeletal growth is a common occurrence in all forms of OI, with most patients falling below the third percentile for height. Achieving normal height is rare, and it usually happens only in cases of mild disease. Although the severity of the deformities plays a role, some studies have noted that reduced height can occur regardless of the frequency of fractures. For those severely affected, growth can virtually halt after the age of 3 or 4, with adults of type III potentially not growing taller than 3 feet. In less severely affected individuals, a modest growth spurt may occur prior to puberty. However, the impacts of scoliosis, long bone fractures, and deformities can exaggerate what is essentially an inherent defect in the way OI bone responds to normal growth stimuli.

Kindly Let Us Know If This Was helpful? Thank You!