Understanding the psychological aspects of diabetes mellitus is an integral part of the effective management of the disease. Diabetes is a lifelong condition that requires ongoing medical care and self-management[1]. The complexity of diabetes management often leads to significant psychological and emotional burdens on patients.

A holistic biopsychosocial approach to diabetes care involves not just the biological factors related to the disease but also the psychological and social factors that influence disease management[2]. The psychological aspects encompass patients’ cognitive and emotional responses to their diagnosis, their adherence to therapeutic interventions, and their long-term outlook[3].

Various psychological frameworks have been proposed to better understand these responses. For instance, the Common-Sense Model (CSM) suggests that patients’ illness representations, including their understanding and beliefs about the disease, can significantly impact their self-management behaviors and health outcomes[4]

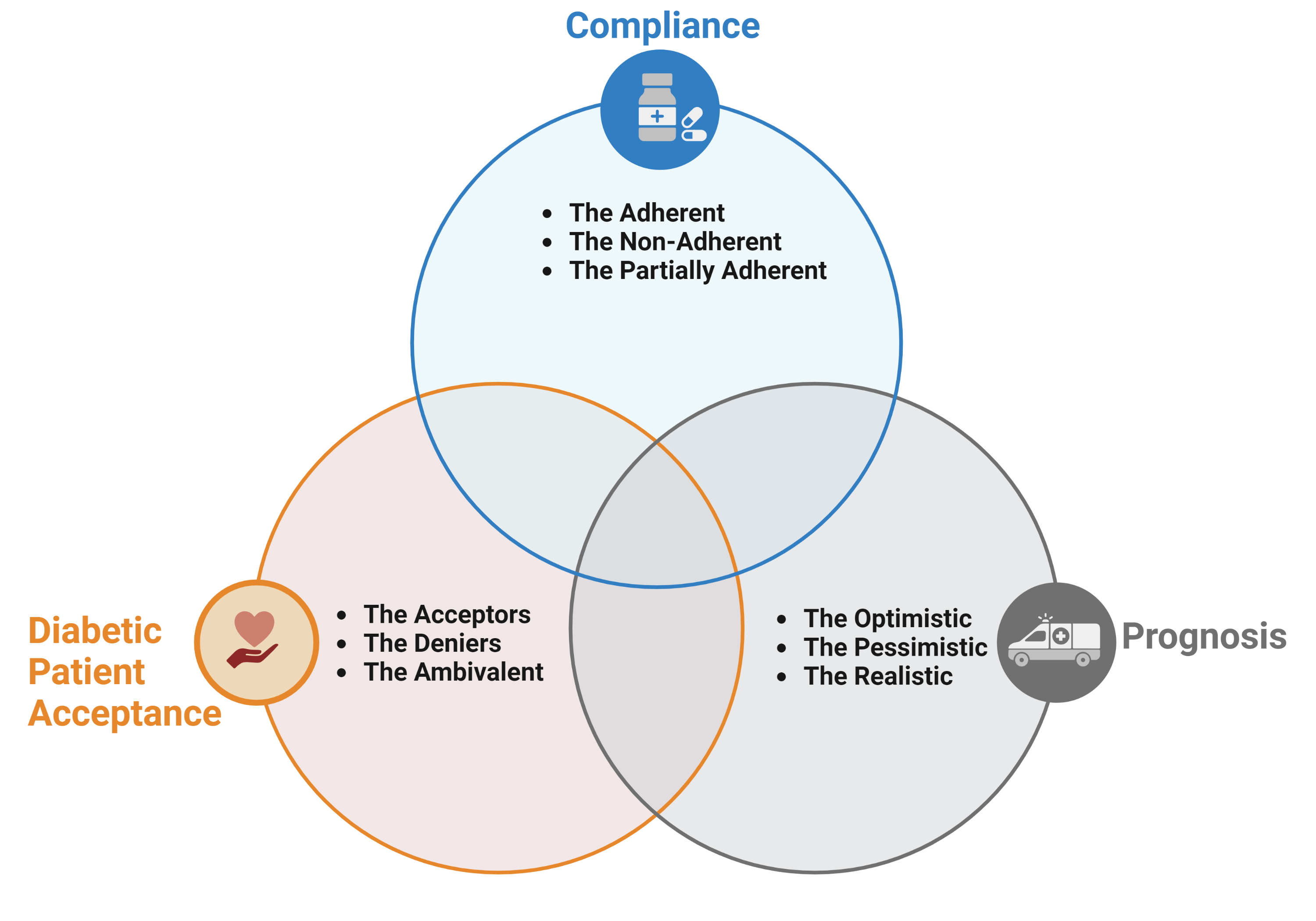

The DiPAC-Pro Model (Diabetic Patient Acceptance, Compliance, and Prognosis Model) expands on this perspective, dividing patients into categories based on their acceptance of diagnosis, compliance with therapy, and long-term outlook (Acceptors vs. Deniers vs. Ambivalent, Adherent vs. Non-Adherent vs. Partially Adherent, Optimistic vs. Pessimistic vs. Realistic).

This stratification aids healthcare providers in tailoring their approach to meet each patient’s specific needs and facilitate more effective management.

Ultimately, an integrated model addressing the psychological aspects of diabetes care, in conjunction with the physical aspects, can lead to improved clinical outcomes and better quality of life for patients living with diabetes [2].

The Proposed DiPAC-Pro Model

The DiPAC-Pro Model (Diabetic Patient Acceptance, Compliance, and Prognosis Model) is a novel psychological framework designed to understand and classify the behaviors and attitudes of patients diagnosed with diabetes.

Acceptance of the diagnosis

This phase focuses primarily on understanding how patients react and adjust to the initial news of their diabetes diagnosis. It examines the diagnosis’s initial emotional and cognitive processing and categorizes patients into three groups based on acceptance: Acceptors, Deniers, and Ambivalent.

The Accepters:

The acceptors are individuals who quickly acknowledge their condition upon diagnosis. Their response to the diagnosis is characterized by a willingness to embrace the reality of their health situation and a readiness to modify their lifestyle to manage their diabetes effectively.

In this context, acceptance is not merely about acknowledging the diagnosis but also about assimilating the condition into their self-concept and recognizing its implications for their present and future well-being. The Acceptors understand that their lives may change, but they perceive this change as an opportunity for growth rather than a threat.

This acceptance can be due to various factors. For some, their previous knowledge about the disease facilitates acceptance. They may already understand the disease process, its management, and its long-term implications. For others, it could be a personal or family history of diabetes that makes the diagnosis less shocking and more familiar. Additionally, a supportive social network, such as family or friends, can contribute to rapid acceptance of the diagnosis.

Importantly, acceptors are open to learning and adapting and actively seek information about diabetes. They tend to ask questions about their health condition and are more likely to follow up with medical advice than other groups. Ultimately, they understand the importance of diet, exercise, medication, and regular monitoring in managing their condition.

Understanding the behaviors and motivations of the acceptors provides an invaluable opportunity for healthcare professionals to encourage and foster these attitudes. By providing adequate support, resources, and affirmation, healthcare providers can strengthen positive adaptive behaviors, potentially leading to improved disease management and a better quality of life.

The Deniers:

Deniers are characterized by a refusal to acknowledge their diagnosis of diabetes, often due to feelings of fear, shock, or disbelief. These patients perceive a diagnosis of diabetes mellitus as a threat to their self-image, way of life, or even their plans. This denial can sometimes serve as a psychological defense mechanism, helping them avoid the anxiety, stress, or potential changes in lifestyle associated with the condition.

It should be noted that these patients may not necessarily deny the factual basis of the diagnosis. However, they may downplay its significance, question the need for lifestyle changes, or be reluctant to start medical intervention. Denial can be conscious (deliberate avoidance) or unconscious (unaware of their avoidance behavior), causing a delay in the initiation of treatment or inconsistent adherence to prescribed therapies.

The Deniers’ reluctance to acknowledge their diagnosis poses significant challenges for disease management. A delay in treatment or poor adherence to therapy can lead to uncontrolled diabetes and increase the risk of microvascular and macrovascular complications.

Healthcare providers working with Deniers may need to adopt a sensitive and supportive approach, starting with a slow introduction of information, reassurance, and psychological support. This could include individual counseling, patient education programs, or support groups that can help these patients gradually come to terms with their diagnosis.

The ultimate therapeutic goal with the Deniers is to facilitate a process of gradual acceptance, helping them confront their repressed fears about their diagnosis. Doing so might make it possible to transform denial into acceptance and non-adherence into active participation in diabetes care.

The Ambivalent:

In the DiPAC-Pro model, the third group of patients in the acceptance phase is categorized as the “Ambivalent.” The Ambivalent group consists of patients who exhibit mixed feelings or conflicting attitudes about their diagnosis of diabetes. Unlike the Acceptors who readily accept their diagnosis or the Deniers who outright refuse to acknowledge it, the Ambivalent fluctuates between acceptance and denial.

These patients may recognize the reality of their condition. However, at the same time, they are grappling with apprehension, uncertainty, or emotional discomfort about the implications of their diagnosis. They may have periods where they readily engage in self-management behaviors, such as adherence to medication or dietary changes, followed by periods of avoidance or, worse still, denial.

This ongoing internal conflict may result in inconsistent self-care practices, irregular medical visits, and a lack of steady progress in disease management. As a result, the Ambivalent group, like the denial group, is particularly prone to poor glycemic control and an increased risk of complications associated with diabetes.

Effective healthcare intervention for the Ambivalent group requires a patient-centered approach that addresses the emotional and practical aspects of disease management. On the one hand, clinicians can employ techniques such as motivational interviewing to address ambivalence, improve acceptance, and improve diabetes self-care. On the other hand, it is crucial to provide these patients with appropriate educational resources and self-management tools.

Over time, the goal for the Ambivalent group would be to resolve their internal conflict and achieve a state of acceptance, where they are able to integrate the diagnosis into their sense of self consistently. Doing so would likely lead to better compliance with treatment and a better long-term prognosis.

Compliance with therapy

Compliance or adherence to therapy involves following medical advice on medication, diet, and lifestyle changes. We can categorize patient compliance into three types:

The Adherent

The adherent group consists of patients who, upon receiving their diagnosis of diabetes and subsequent management plan, commit to following the recommended treatment regimen with diligence and consistency. They understand the importance of consistent compliance in managing their condition and preventing or delaying complications.

Adherence to this group extends beyond just taking prescribed medications. These individuals also make necessary lifestyle modifications, such as maintaining a healthy diet, incorporating regular physical activity, managing stress, and abstaining from harmful behaviors such as smoking or excessive alcohol consumption. They monitor their blood sugar levels as recommended and maintain regular appointments with healthcare providers.

The Adherent group shows a strong sense of responsibility for their health. Their behaviors indicate acceptance of their condition and a willingness to do what is necessary to manage it effectively. Their actions are often driven by a desire to maintain health, avoid complications, and ensure the best possible quality of life.

However, it is essential to recognize that even within the Adherent group, levels of adherence can vary, and maintaining a high level of adherence can be challenging due to various factors. These can include the treatment regimen’s complexity, other health conditions, socioeconomic factors, and the level of support from healthcare providers, family, and friends.

For healthcare providers, recognizing and supporting the behaviors of the Adherent group is crucial. This could involve providing positive reinforcement, continuing education to maintain up-to-date knowledge about diabetes management, and offering the necessary resources and support for potential challenges that may impact adherence.

The Non-Adherent

The non-adherent group is comprised of patients who struggle to consistently follow the recommended treatment regimen for managing their diabetes. This can include not taking medications as prescribed, not following dietary guidelines, not engaging in regular physical activity, and neglecting regular monitoring of blood glucose levels.

Non-adherent patients often display erratic patterns in following their treatment plans or may completely neglect their self-care routines. Their non-compliance can stem from various reasons such as denial or ambivalence about the diagnosis, lack of understanding about the disease, fear of the potential side effects of medication, financial constraints, lack of access to healthcare resources, or lack of support from their social environment.

Identifying non-adherent patients is critical for healthcare providers due to the significant risks associated with poor diabetes management, including serious health complications and reduced quality of life. This group may require additional support and intervention to improve adherence.

Interventions may include patient education to improve understanding of the disease and its management, behavioral counseling to address fears or misconceptions, developing a simplified treatment plan, improving access to healthcare resources, or introducing social support systems.

The Partially Adherent:

They exhibit inconsistent adherence to their diabetes management plan. Unlike the Adherent patients who follow the treatment regimen closely or the Non-Adherent who mostly or entirely ignore it, the Partially Adherent group falls somewhere in between.

These patients may follow certain aspects of their treatment regimen while neglecting others. For example, they might take their medications regularly but struggle with implementing dietary changes or regular exercise. Alternatively, they may follow their regimen strictly during specific periods but lapse during stress, illness, or significant life changes.

Several factors can contribute to partial adherence. It might be due to a lack of understanding of the disease, a lack of resources, the complexity of the treatment regimen, perceived side effects, or emotional factors such as fear, anxiety, or depression. In some cases, it could be due to a lack of belief in the efficacy of the treatment or a fractured patient-physician relationship.

Healthcare providers can assist the Partially Adherent group by identifying the barriers preventing full adherence and addressing them directly. This could involve additional patient education, simplifying the treatment regimen, addressing emotional concerns, or connecting the patient with additional resources for support.

The goal is to help these patients navigate their partial adherence toward more consistent compliance with therapy, ultimately promoting better disease management and health outcomes.

The prognosis (Long-Term Outlook)

The long-term outlook or prognosis involves the patient’s perception of their future living with diabetes. We can classify this outlook into three types:

The Optimistic

The Optimistic group comprises patients with a positive outlook on their long-term prognosis despite their diagnosis of diabetes. They maintain hope and confidence in managing their condition effectively and leading fulfilling lives. This optimism often extends from their acceptance of the diagnosis and adherence to the prescribed treatment regimen, instilling a belief that they have significant control over their condition.

The Optimistic group sees their diabetes not as a debilitating condition but a manageable part of their life. They believe that making the right choices regarding their diet, physical activity, and medication can maintain a good quality of life and prevent or delay the onset of complications.

Optimism, while beneficial for mental well-being, should be accompanied by a realistic understanding of the condition. For healthcare professionals, it is crucial to ensure that this optimism doesn’t lead to complacency in disease management. Regular follow-ups, continuous education, and ongoing encouragement can help these patients maintain their positive outlook while also staying vigilant about their health management.

Overall, the Optimistic group highlights the importance of a positive outlook on disease prognosis. Their attitudes testify to the importance of psychological factors in managing chronic illnesses like diabetes.

The Pessimistic

The Pessimistic group includes patients with a negative outlook on their long-term prognosis. These individuals may feel overwhelmed by the chronic nature of the disease and often view the diagnosis as a significant setback to their life’s plans and aspirations. This can result in despair, hopelessness, or resignation about the future.

The Pessimistic group may struggle to see the potential for a satisfying and fulfilling life while managing their diabetes. This negative outlook may hinder their ability to engage in proactive disease management and could influence their treatment adherence.

Identifying the Pessimistic group is critical for healthcare providers as this negative outlook can significantly impact the patient’s overall well-being and health outcomes. It’s essential to address these feelings of pessimism through interventions that can improve their mood and shift their perspective towards a more positive and hopeful outlook.

Psychotherapy, particularly cognitive-behavioral therapy, may be beneficial for these patients to challenge and change their negative thought patterns. Additionally, patient education about the disease and its management, along with sharing success stories and positive role models, could help instill a sense of possibility and control.

Ultimately, the goal is to guide these patients towards a balanced understanding of their disease: while diabetes is indeed a serious condition, it can be effectively managed, and a fulfilling life is still very much possible. This gradual shift in perspective can contribute to a more constructive approach to disease management and improved health outcomes.

The Realistic

The Realistic group consists of patients who maintain a balanced and pragmatic perspective on their long-term prognosis with diabetes. They fully comprehend the seriousness of the disease and the necessity for lifelong management. However, instead of being overly optimistic or pessimistic, they understand and accept the challenges and possibilities associated with their condition.

The Realistic group acknowledges that while diabetes is a chronic condition that requires diligent management, it is not an insurmountable obstacle. They recognize the potential risks and complications that can arise from poor management but also appreciate the control they can exercise over their condition through effective self-care and adherence to treatment plans.

From a healthcare provider’s perspective, the Realistic group often represents an ideal patient approach toward chronic disease management. These individuals are typically proactive about their health, vigilant about their self-care practices, and open to learning more about their condition.

Nevertheless, providing continuous support and reinforcement to this group remains crucial. Healthcare providers should appreciate their realistic perspective, which can be a driving force for consistent self-management, but also remain vigilant about any potential fluctuations in their disease management behavior or overall outlook.

In essence, the Realistic group provides a useful example of the balanced psychological adaptation possible in the context of chronic diseases like diabetes. Their approach underscores the importance of psychological resilience and acceptance in achieving optimal health outcomes.

Each patient may shift between these categories in each phase over time, impacted by various biological factors (like disease progression or treatment side effects), psychological factors (like mental health or cognitive abilities), and social factors (like family support or healthcare access). Healthcare professionals can utilize the DiPAC-Pro Model to understand patients’ attitudes and behaviors and subsequently tailor education, support, and interventions based on these insights.

The DiPAC-Pro Model, as proposed, identifies three main categories for each phase: acceptance of diagnosis (Acceptor, Denier, Ambivalent), compliance with therapy (Adherent, Non-Adherent, Partially Adherent), and long-term outlook (Optimistic, Pessimistic, Realistic). Thus, there are, theoretically, 27 possible groupings when considering all combinations of these categories.

However, I have focused on a few specific combinations representing the broad spectrum from the best to the worst clinical outcomes. For example, some combinations, like the Denier-Adherent-Optimistic group, may seem contradictory or unlikely, but they are theoretically possible.

For example, a patient might deny the seriousness of their condition (Denier) but still adhere to their prescribed treatment (Adherent) because they trust their healthcare provider or due to the influence of their support system. They might also maintain an optimistic outlook because their denial prevents them from fully recognizing the potential risks and complications associated with their diabetes.

Therefore, while not all combinations might be commonly encountered in clinical practice, healthcare providers must remain open to the complexity and variability of patients’ psychological responses and behaviors in managing their diabetes. Each patient’s journey is unique, and their position within the proposed DiPAC-Pro Model may shift over time as they navigate their diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management.

Categorization of patients based on the DiPAC-pro model

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the categories of patients based on the DiPAC-pro model.

Table 1. Selected Contextual categories of patients based on the DiPAC-pro model

| DiPAC-pro category | Description |

| Adherent-Acceptor-Optimistic (AAO) group | These individuals accept their diagnosis, consistently adhere to their treatment regimen, and maintain an optimistic outlook. They are likely to have the best clinical outcomes due to their full acceptance of the condition, regular compliance with treatment, and a positive perspective on their ability to manage the disease effectively. |

| Adherent-Acceptor-Realistic (AAR) group | This group also accepts their diagnosis and complies with their treatment regimen. They have a realistic outlook on their prognosis. While they may not be as inherently optimistic as the AAO group, their understanding of the disease’s realities and their consistent compliance with treatment place them in a strong position for favorable outcomes. |

| Partially Adherent-Acceptor-Realistic (PAR) group | Patients in this group accept their diagnosis but have variable compliance with their treatment regimen. They maintain a realistic outlook on their prognosis. Their inconsistent adherence may lead to less optimal outcomes than the AAO or AAR groups. |

| Adherent-Ambivalent-Optimistic (AAmO) group: | This group adheres to their treatment plan but has not fully accepted their diagnosis. Their optimistic outlook may contribute to their adherence. However, their ambivalence about the diagnosis could lead to emotional distress and pose risks for long-term treatment consistency. |

| Partially Adherent-Ambivalent-Realistic (PAAmR) group | This group shows partial adherence to treatment and a realistic outlook on their prognosis. Their ambivalence about the diagnosis could impact their treatment consistency and emotional well-being. |

| Non-Adherent-Acceptor-Pessimistic (NAP) group | Despite accepting their diagnosis, these individuals do not adhere to their treatment regimen and have a pessimistic outlook. Their lack of compliance and a negative perspective might result in poor clinical outcomes. |

| Non-Adherent-Denier-Pessimistic (NDP) group | This group represents the worst clinical outcomes. They neither accept their diagnosis nor adhere to treatment and maintain a pessimistic view of their prognosis. Their denial, non-adherence, and negative outlook could lead to severe health complications. |

This categorization system aims to provide a guideline for healthcare providers to assess the likely trajectory of a patient’s disease management based on their psychological adaptation and behavior. However, it is crucial to remember that individuals are complex and unique. Effective patient care should involve ongoing assessment, communication, and personalized interventions, as patients may shift between these categories over time.

Incorporating Behavioral changes in the DiPAC model

The Behavior Change Wheel, a theory-driven intervention framework developed by Michie et al. [5], provides a helpful structure for addressing the behavioral challenges identified in the DiPAC-Pro Model. The Behavior Change Wheel includes three components: Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation (COM-B), which interact to result in the performance of a specific behavior.

Capability refers to the patient’s psychological and physical capacity to engage in the activity, including the necessary knowledge and skills.

Opportunity refers to all the factors outside the individual that make a particular behavior possible or even prompt it.

Finally, the motivation component of the COM-B frameworks involves all the brain processes that energize and direct behavior, including habitual processes, emotional responses, and analytical decision-making.

Applying this model to address the various challenges within the DiPAC-Pro Model can provide a systematic approach to improve diabetes management outcomes.

Table 2.

| COM-B Framework | DiPAC-Pro Model | ||

| Acceptance | Compliance | Long term outlook | |

| Capability | Educational programs can enhance the understanding of diabetes, its causes, its implications, and the importance of acceptance. This understanding can help patients transition from being Deniers or Ambivalent to becoming Acceptors. | Training on practical skills, such as self-monitoring blood glucose or administering insulin injections, can improve adherence. | Psychoeducation can help individuals develop healthier outlooks, moving from pessimism to either Realistic or Optimistic. |

| Opportunity | Establishing support groups can help individuals feel less alone and more understood, promoting acceptance. | Reducing barriers to medication access or simplifying complex regimens can improve adherence. | Providing ongoing patient-centered care, where patients actively participate in their care planning, can encourage a more Realistic or Optimistic outlook. |

| Motivation | Motivational interviewing can help patients to resolve their ambivalence about the diagnosis and enhance their intrinsic motivation to accept it. | Enhancing motivation through positive reinforcement, such as recognizing and celebrating patients’ progress, can improve adherence. | Cognitive-behavioral strategies can address pessimistic attitudes and promote a more Realistic or Optimistic outlook. |

To create an intervention using the COM-B and BCW frameworks, it’s crucial first to conduct a thorough assessment to identify the specific challenges each patient (or patient group) faces. Based on this assessment, the most relevant and effective interventions can be designed and implemented. Over time, these interventions should be evaluated and refined as necessary, creating an iterative process of continuous improvement.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the DiPAC-Pro Model offers an innovative and comprehensive approach to understanding and addressing the psychological challenges associated with managing diabetes mellitus. By stratifying patients into categories based on their acceptance of diagnosis, compliance with therapy, and long-term outlook, this model enables a more nuanced understanding of individual patient experiences and behaviors.

The DiPAC-Pro model considers not just the outward behaviors of patients but also the subconscious and conscious thought processes that influence those behaviors. This allows healthcare professionals to consider a patient’s emotional and psychological state along with their physical condition in a truly biopsychosocial approach to diabetes care.

The integration of the COM-B model into the framework further enables the development of targeted interventions to enhance patients’ capabilities, opportunities, and motivation to manage their condition. In essence, the DiPAC-Pro Model serves as a dynamic tool for personalizing diabetes care and improving outcomes.

However, the application of this model requires further empirical testing for its efficacy and potential modification based on real-world patient data. In particular, it’s crucial to explore whether interventions tailored to the model’s categories result in better diabetes management and improved patient quality of life.

Download the DiPAC-Pro Model Questionnaire

References

1. American Diabetes Association (2018) Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2018 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. Clinical Diabetes, 36 (1), 14–37.

2. Fisher, L., Skaff, M.M., Mullan, J.T., Arean, P., Mohr, D., Masharani, U., Glasgow, R., and Laurencin, G. (2007) Clinical depression versus distress among patients with type 2 diabetes: not just a question of semantics. Diabetes Care, 30 (3), 542–548.

3. Peyrot, M., and Rubin, R.R. (2007) Behavioral and Psychosocial Interventions in Diabetes: A conceptual review. Diabetes Care, 30 (10), 2433–2440.

4. Leventhal, H., Diefenbach, M., and Leventhal, E.A. (1992) Illness cognition: Using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cogn Ther Res, 16 (2), 143–163.

5. Michie, S., van Stralen, M.M., and West, R. (2011) The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6 (1), 42.

Kindly Let Us Know If This Was helpful? Thank You!