People with diabetes are at a higher risk for various foot health problems; therefore, a thorough foot examination is important. This involves self-foot monitoring daily and yearly professional evaluations. The risk of developing foot disorders that could lead to major complications can be avoided by following preventive measures (1).

Neuropathy, the leading cause of foot ulcers, is common in people with diabetes. Due to the sensory loss from diabetic neuropathy, a foot injury could go unnoticed until the symptoms are severe.

Furthermore, a reduced arterial flow to the wound site can make infections take longer to heal. Taking good care of your feet and seeking medical attention for a developing condition can prevent symptoms from getting worse, and more severe procedures like amputation can be avoided (2).

In addition to offering diabetes foot care guidelines, this article outlines the suggested indications for clinical examination of a diabetic foot that is intended for healthcare providers, medical students, and practitioners.

The patient History

In order to make an accurate diagnosis, it is essential to review the patient’s medical history. Before starting the foot exam, a healthcare professional would ask the patient about diabetes, their approach to managing it, or any other previous complications that a patient has had with their feet. The doctor might also inquire about smoking history; according to research, smoking can cause further foot complications such as circulation issues and nerve damage (3).

It is also required to ask the patients about their medication history, the quality of peripheral protective sensation, and how long their foot wounds take to heal.

The main objective in diabetic foot care is the implementation of various preventive techniques, such as patient education, involvement, and adherence to medical recommendations.

Strong evidence suggests that a lack of appropriate education regarding diabetes contributed to more than 90% of recurrent foot ulcers, highlighting the importance of ongoing education for at-risk patients (4).

Primary healthcare workers should teach patients about the importance of foot screenings and proper diabetic foot care to reduce the likelihood of complications.

Preparing the patient for the foot exam

Before proceeding with the clinical examination, it is essential to gain consent from the patients and ask them if they have any pain.

The first step is to expose the patient’s lower limbs adequately; for this, diabetic patients should take off their shoes and socks. The feet should be properly cleaned and dry prior to checkups or dressing changes on a diabetic foot ulcer. To reduce the risk of contamination and infection, patients should set up a clean and hygienic environment (5).

Components of the diabetic foot exam

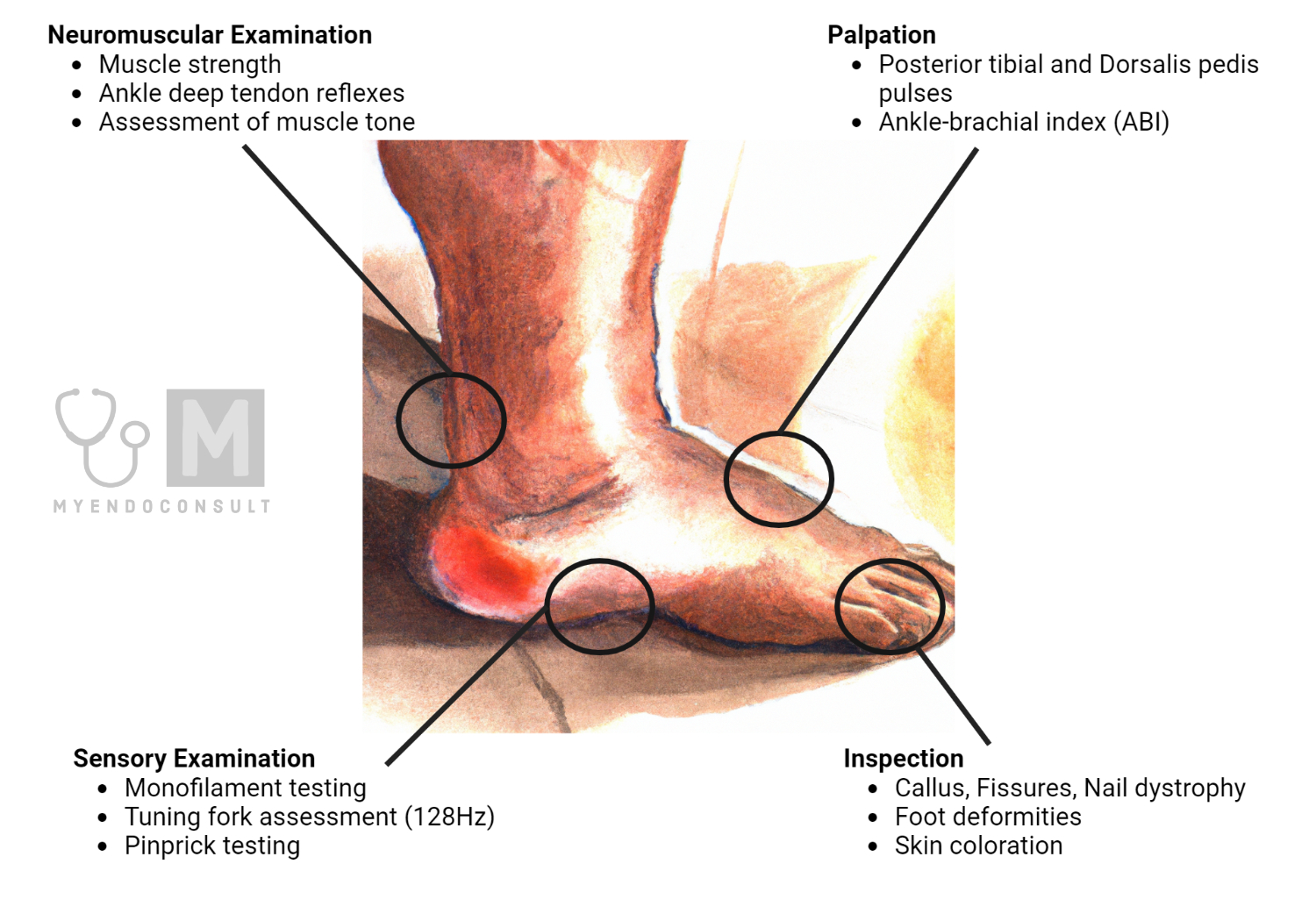

There are four main components of a lower limb physical examination: dermatological, vascular, neurological, and musculoskeletal.

Inspection

For patients with confirmed or suspected diabetes, the clinical examination begins with a careful inspection of the feet.

The dermatologic exam serves as an indicator for early intervention and frequently leads to referral to a specialist. It begins with a general inspection for discoloration, calluses, wounds, fissures, interdigital macerations, nail dystrophy, or paronychia. Skin color changes and hair growth loss may be the initial indicators of vascular insufficiency, while calluses and hypertrophic skin are usually precursors to ulcers (6).

Checking the toes for fungus, ingrown hairs, or extended nails is important. The spaces between toes should be examined carefully because there could be an unnoticed interdigital infection. Besides that, a temperature difference of more than 3 to 4 degrees from the contralateral foot may be evidence of infection or acute Charcot neuroarthropathy (7, 8).

Furthermore, it is vital to inquire about foot deformity as it contributes to ulcer development. It is generally believed that foot abnormalities in diabetic patients result from motor neuropathy. The structural foot deformities that are frequently observed include hallux valgus, pes cavus, pes equinus, claw and hammer toes, and prominent metatarsal heads.

While hallux rigidus and limitus are the functional foot abnormalities that are commonly reported (9).

Several studies suggest that foot deformities did not clearly correlate with intrinsic foot muscle atrophy (IFMs), muscular imbalance, or a decline in nerve function. However, muscular weakness and limited joint mobility were found to be associated with these abnormalities in diabetic patients (10).

Palpation

In healthy people, the lower limbs should be evenly warm, indicating appropriate perfusion. At the same time, poor arterial perfusion is indicated by a cold and pale limb. In order to quickly evaluate peripheral perfusion, palpate the dorsalis pedis (located over the dorsum of the foot) and posterior tibial pulses (11).

Then compare the pulse strength between the feet. A decrease in pedal pulses may call for testing for peripheral arterial disease using a Doppler ultrasound (12).

A Doppler ultrasound of pedal arteries can indicate triphasic flow, which is normal; biphasic flow, which shows mild arterial disease, monophasic flow, which indicates peripheral arterial disease (PAD) with a risk of limb ischemia; or absent, which indicates severe PAD with a significant risk of ischemia and limb loss (13).

The non-invasive procedures such as pulse volume recording, toe pressures, ankle-brachial index (ABI), and segmental pressures can also assess the level of peripheral vascular disease (14). A referral to vascular surgery should be followed if these evaluations reveal any signs of PAD.

Sensory Examination

The diabetic foot sensory exam consists of monofilament, tuning fork, and pinprick testing.

Semmes-Weinstein monofilament is the frequently used instrument for testing pressure or touch sensation. According to various studies, the 5.07/10-g monofilament is the most reliable indicator for detecting protective sensation loss. The typical examination takes over 2 minutes. Each foot should be tested at the following ten sites: the distal first, third, and fifth toe; the plantar first, third, and fifth metatarsal heads; the plantar medial and lateral arch; the plantar heel, and the dorsal first interspace. The perception of 6 or fewer sites out of 10 is considered abnormal. Scars and calluses should be avoided since they have decreased sensation that is not representative of the surrounding tissue (15).

The 128-Hz standard tuning fork is used to assess vibratory sensation, and if the patient can no longer detect vibration, the result may indicate diabetic neuropathy (16).

A sterile or unused sharp pin device can be used to perform the pinprick over the plantar aspect of the distal first, third, and fifth toe of each foot. The stimulus is applied once per site, and it tests the patient’s ability to discern between sharp and dull sensations.

Due to the loss of protective sensation, patients are at a greater risk of unrecognized injury. As a result, skin breakdown may progress to ulceration that requires amputation. Therefore, in order to assess nerve damage (peripheral neuropathy), these tests are cost-effective, and instruments are portable and easy to use, especially in primary care (17).

Moreover, these tests, in combination, have greater than 87% sensitivity in detecting diabetic peripheral neuropathy and also have a predictive validity of ulceration and amputation.

Neuromuscular examination

Diabetic patients are more likely to develop musculoskeletal deformities such as a hammer toe, claw toe, or a bunion which can cause substantial pain and/or gait impairment, as well as increase an additional risk for friction-induced skin breakdown and ulceration.

It has been reported that diabetic neuropathy leads to sarcopenia (decrease in muscle mass and muscle strength). Furthermore, depending on the degree of diabetic polyneuropathy, a greater decrease in knee extension force was reported. A neuropathic patient may have elevated plantar foot pressures and tissue breakdown as a result of a flexible ankle equinus brought on by gastrocnemius tightness (18, 19).

For the clinical evaluation of foot muscle atrophy in diabetic patients, ultrasonography has been reported to be a helpful tool. Scientific evidence suggests that foot muscle atrophy, which reflects motor dysfunction, is directly related to the severity of neuropathy (20).

A manual method is used to examine the muscle strength, which involves measuring the strength of the patient’s key muscles in the upper and lower extremities against the examiner’s resistance and evaluating it from 0 to 5 scale. Grade 0 represents no muscle activation, while grade 5 indicates muscle activation against the examiner’s full resistance and achieving full range of motion. A practitioner can test muscle strength to identify complicated neurologic impairment (21).

Various studies indicate that patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy may also exhibit an absent ankle reflex. Therefore, the use of a knee hammer for performing the ankle reflex is a powerful screening tool in clinical practice. This has been pathologically attributed to various changes in both myelinated and unmyelinated fibers in peripheral neuropathy, whereas Schwann cell modifications might be the main pathologic change (22).

Besides that, muscle tone can be assessed by observing how a muscle reacts to passive stretching in order to test this, flex and extend the patient’s elbow, wrist, knee, and ankle joints. A decreased muscle resistance was found in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy (23).

In order to make a proper diagnosis, it is therefore crucial that lower extremity muscular strength and foot or ankle abnormalities must be determined through a musculoskeletal assessment. Also, to define the appropriate treatment, the flexibility and rigidity of the joint range of motion should be examined properly.

Footwear Assessment

According to different studies, footwear has been linked to the development of diabetic ulcers, with an estimated 74% of patients with diabetes wearing improperly fitted shoes that ultimately lead to foot amputation. It is, therefore, important to carefully examine the patient’s footwear (24).

Start by determining whether the patient’s shoes are medicated or normal. Examine the wear pattern, which typically affects the outside of the shoe heel. Different wear patterns show inappropriate foot contact with the ground. A supination deformity is indicated by early lateral, proximal, and midfoot shoe wear; a pronation deformity is indicated by medial border wear. The absence of any wear may simply indicate an unused pair of foot wears (25).

It must be checked that the shoe size is accurate for the patient. Moreover, understanding the materials used in shoes helps with advice, especially when considering the patient’s activity and health. In older adults, the sole material has been linked to slips and falls, so altering this component of the shoe may be essential for the patient’s care (26).

It is commonly known that high-heeled shoes are uncomfortable and inappropriate for daily wear. Therefore, it is advised to use heels between 1 and 4 cm in height to maintain stability because heels under 0.5 cm can make it harder to maintain balance. Hence, when giving guidance, a clinical assessment and evaluation of heel height, heel drop, and sole thickness are relevant (27).

One feature that makes the footwear suitable for diabetic individuals and helps prevent ulcers is the fastening of the shoe. Further, cushioning insoles appear to be preferable for clinical intervention in diabetic patients and for lowering metatarsal pressure (28, 29).

During the clinical examination, special consideration must be given to an itchy diabetic foot since itchiness brought on by dry skin, skin disease, or arteriopathy may appear before a skin lesion. There is a significant risk of infection or even amputation in this situation. Diabetic neuropathy could be another reason which causes tingling and burning sensations in the nerves; hence people with diabetes get itchy feet (30) (31).

Further Assessments and Investigations

Foot ulceration, which is frequently associated with peripheral neuropathy, is also a primary risk factor for infections. The predominant pathogens in diabetic foot infections are aerobic gram-positive cocci, particularly Staphylococcus aureus. Additionally, patients with foot ischemia or gangrene may have obligate anaerobic pathogens.

In all cases of infection, send properly acquired specimens for culture before starting empirical antibiotic therapy (32). An alternative to wound swab specimens is tissue collected through biopsy, ulcer curettage, or aspiration. In addition to this, a bone biopsy helps establish the diagnosis of osteomyelitis (33).

Imaging tests are typically required to detect pathological abnormalities in bone and may aid in diagnosing deep, soft-tissue purulent collections. Conventional radiography may be sufficient in many conditions, but MRI is more sensitive and specific than isotope scanning, especially for detecting soft-tissue lesions (34).

An ulcer may result from changes in the alignment of the bones in the foot, which can be evaluated via X-ray imaging. X-rays can also show a reduction in bone mass caused by hormonal imbalances in diabetes (3).

Decreased bone mass weakens bones, which can result in Charcot foot (repeated tiny fractures and other foot injuries). Therefore, early diagnosis of this issue will help prevent the foot bones from being permanently misaligned, which can stop the development of new ulcers (35).

Blood tests, including the WBC count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein level, are frequently performed to aid in diagnosis and to screen for infection if the affected foot exhibits symptoms such as redness, swelling, and warmth.

It has been shown that diabetic foot ulceration is associated with elevated C-reactive protein levels. Infection may cause an increase in hemoglobin A1c and blood sugar levels, while other acute-phase proteins, including ferritin, 1-antitrypsin, and haptoglobin, are currently being studied (36).

A combination of clinical and radiological assessments must be employed together with laboratory tests to diagnose a diabetic foot infection properly.

References

- Bild DE, Selby JV, Sinnock P, Browner WS, Braveman P, Showstack JA. Lower-extremity amputation in people with diabetes: epidemiology and prevention. Diabetes care. 1989;12(1):24-31.

- Tsao T. Diabetic foot care. Diabetic Foot Problems: World Scientific; 2008. p. 503-26.

- Ahmad J. The diabetic foot. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews. 2016;10(1):48-60.

- Miller JD, Carter E, Shih J, Giovinco NA, Boulton AJ, Mills JL, et al. How to do a 3-minute diabetic foot exam: this brief exam will help you to quickly detect major risks and prompt you to refer patients to appropriate specialists. Journal of Family Practice. 2014;63(11):646-54.

- Boulton AJ. The diabetic foot. Medicine. 2019;47(2):100-5.

- Fard AS, Esmaelzadeh M, Larijani B. Assessment and treatment of diabetic foot ulcer. International journal of clinical practice. 2007;61(11):1931-8.

- van Netten JJ, Prijs M, van Baal JG, Liu C, van Der Heijden F, Bus SA. Diagnostic values for skin temperature assessment to detect diabetes-related foot complications. Diabetes technology & therapeutics. 2014;16(11):714-21.

- Johnson R, Osbourne A, Rispoli J, Verdin C. The diabetic foot assessment. Orthopaedic Nursing. 2018;37(1):13-21.

- Khan T, Armstrong DG. The musculoskeletal diabetic foot exam. Diabetic Foot J. 2018;21(1):17-28.

- Allan J, Munro W, Figgins E. Foot deformities within the diabetic foot and their influence on biomechanics: A review of the literature. Prosthetics and orthotics international. 2016;40(2):182-92.

- Kunkler CE. Neurovascular assessment. Orthopaedic Nursing. 1999;18(3):63-71.

- Khan NA, Rahim SA, Anand SS, Simel DL, Panju A. Does the clinical examination predict lower extremity peripheral arterial disease? Jama. 2006;295(5):536-46.

- Bashar AHM, Ahmed M. Peripheral Vascular Disease: A Contemporary Review. Bangladesh Heart Journal. 2019;34(2):137-45.

- Begelman SM, Jaff MR. Noninvasive diagnostic strategies for peripheral arterial disease. Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine. 2006;73(4):S22.

- Koçer A. How to diagnose neuropathy in diabetes mellitus? The European Research Journal. 2018;4(2):55-69.

- Oyer DS, Saxon D, Shah A. Quantitative assessment of diabetic peripheral neuropathy with use of the clanging tuning fork test. Endocrine Practice. 2007;13(1):5-10.

- Smieja M, Hunt DL, Edelman D, Etchells E, Cornuz J, Simel DL, et al. Clinical examination for the detection of protective sensation in the feet of diabetic patients. Journal of general internal medicine. 1999;14(7):418-24.

- Leenders M, Verdijk LB, van der Hoeven L, Adam JJ, Van Kranenburg J, Nilwik R, et al. Patients with type 2 diabetes show a greater decline in muscle mass, muscle strength, and functional capacity with aging. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2013;14(8):585-92.

- Nishimoto GS, Attinger CE, Cooper PS. Lengthening the Achilles tendon for the treatment of diabetic plantar forefoot ulceration. Surgical Clinics. 2003;83(3):707-26.

- Severinsen K, Obel A, Jakobsen J, Andersen H. Atrophy of foot muscles in diabetic patients can be detected with ultrasonography. Diabetes care. 2007;30(12):3053-7.

- Williams M. Manual muscle testing, development and current use. Physical Therapy. 1956;36(12):797-805.

- Jayaprakash P, Bhansali A, Bhansali S, Dutta P, Anantharaman R, Shanmugasundar G, et al. Validation of bedside methods in evaluation of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. The Indian journal of medical research. 2011;133(6):645.

- Daroff RB, Aminoff MJ. Encyclopedia of the neurological sciences: Academic press; 2014.

- Jorgetto JV, Gamba MA, Kusahara DM. Evaluation of the use of therapeutic footwear in people with diabetes mellitus–a scoping review. Journal Of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders. 2019;18:613-24.

- Alazzawi S, Sukeik M, King D, Vemulapalli K. Foot and ankle history and clinical examination: A guide to everyday practice. World journal of orthopedics. 2017;8(1):21.

- Menant JC, Steele JR, Menz HB, Munro BJ, Lord SR. Optimizing footwear for older people at risk of falls. 2008.

- Bus SA. Foot structure and footwear prescription in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes/metabolism research and reviews. 2008;24(S1):S90-S5.

- Ellis S, Branthwaite H, Chockalingam N. Evaluation and optimisation of a footwear assessment tool for use within a clinical environment. Journal of Foot and Ankle Research. 2022;15(1):12.

- Bus SA, Lavery LA, Monteiro‐Soares M, Rasmussen A, Raspovic A, Sacco IC, et al. Guidelines on the prevention of foot ulcers in persons with diabetes (IWGDF 2019 update). Diabetes/metabolism research and reviews. 2020;36:e3269.

- Kochhar A, Sharma N, Sachdeva R. Effect of supplementation of Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum) and Neem (Azadirachta indica) leaf powder on diabetic symptoms, anthropometric parameters and blood pressure of non insulin dependent male diabetics. Studies on Ethno-Medicine. 2009;3(1):5-9.

- Lockwood W. Wound Management Comprehensive. 2020.

- Lipsky B. Empirical therapy for diabetic foot infections: are there clinical clues to guide antibiotic selection? : Elsevier; 2007. p. 351-3.

- Wheat J. Diagnostic strategies in osteomyelitis. The American journal of medicine. 1985;78(6):218-24.

- Restrepo CS, Giménez CR, McCarthy K. Imaging of osteomyelitis and musculoskeletal soft tissue infections:: current concepts. Rheumatic Disease Clinics. 2003;29(1):89-109.

- Jeffcoate W. Charcot foot syndrome. Diabetic Medicine. 2015;32(6):760-70.

- Rodrı́guez-Morán M, Guerrero-Romero F. Increased levels of C-reactive protein in noncontrolled type II diabetic subjects. Journal of Diabetes and its complications. 1999;13(4):211-5.

Kindly Let Us Know If This Was helpful? Thank You!