Short stature is a general term that applies to children whose height is two standard deviations (SD) or more below the mean for children of that sex, age, and population. Statistics show that 23 per 1000 individuals have this diagnosis. [1] Short stature may be idiopathic, secondary to organ system disease, or arise from an endocrine disorder. Endocrine causes include childhood-onset growth hormone deficiency (GHD), primary insulin-like growth factor 1 deficiency, and defects in their pathways[2].

Etiology/Causes of short stature

Genetic variations in growth must first be considered when searching for a pathological cause of short stature. In other words, children often have similar growth patterns and the onset of puberty as their parents. Therefore a history of pubertal development and evidence of the heights of their family members should be obtained. Moreover, families in which short stature is frequent can show different patterns of growth that are considered normal. One pattern is the constitutional delay of growth and development, where children are known as “late bloomers.”

For pathological short stature, disproportionate short stature means the trunk is longer or shorter in comparison with the limbs. This type is seen in skeletal dysplasias, SHOX gene mutations, or after spine radiation. Proportional short stature refers to an expected trunk length compared to the limbs. This pattern is seen in inherited limitations on bone growth, babies small for the gestational age, genetic and chromosomal abnormalities, or in cases where the mother received radiation during pregnancy that may have affected intrauterine growth.

On the other hand, if a child suffers weight loss or a more progressive decline in weight gain than in linear growth, there may be a nutritional deficiency, malnutrition syndromes such as starvation or anorexia nervosa, malabsorption due to celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or poorly controlled diabetes mellitus. Chronic renal, cardiac, pulmonary, or hematologic diseases can also be the cause. Endocrine system dysfunctions, for instance: growth hormone deficiency, hypothyroidism, or glucocorticoid excess, should be considered as possible etiologies of short stature.

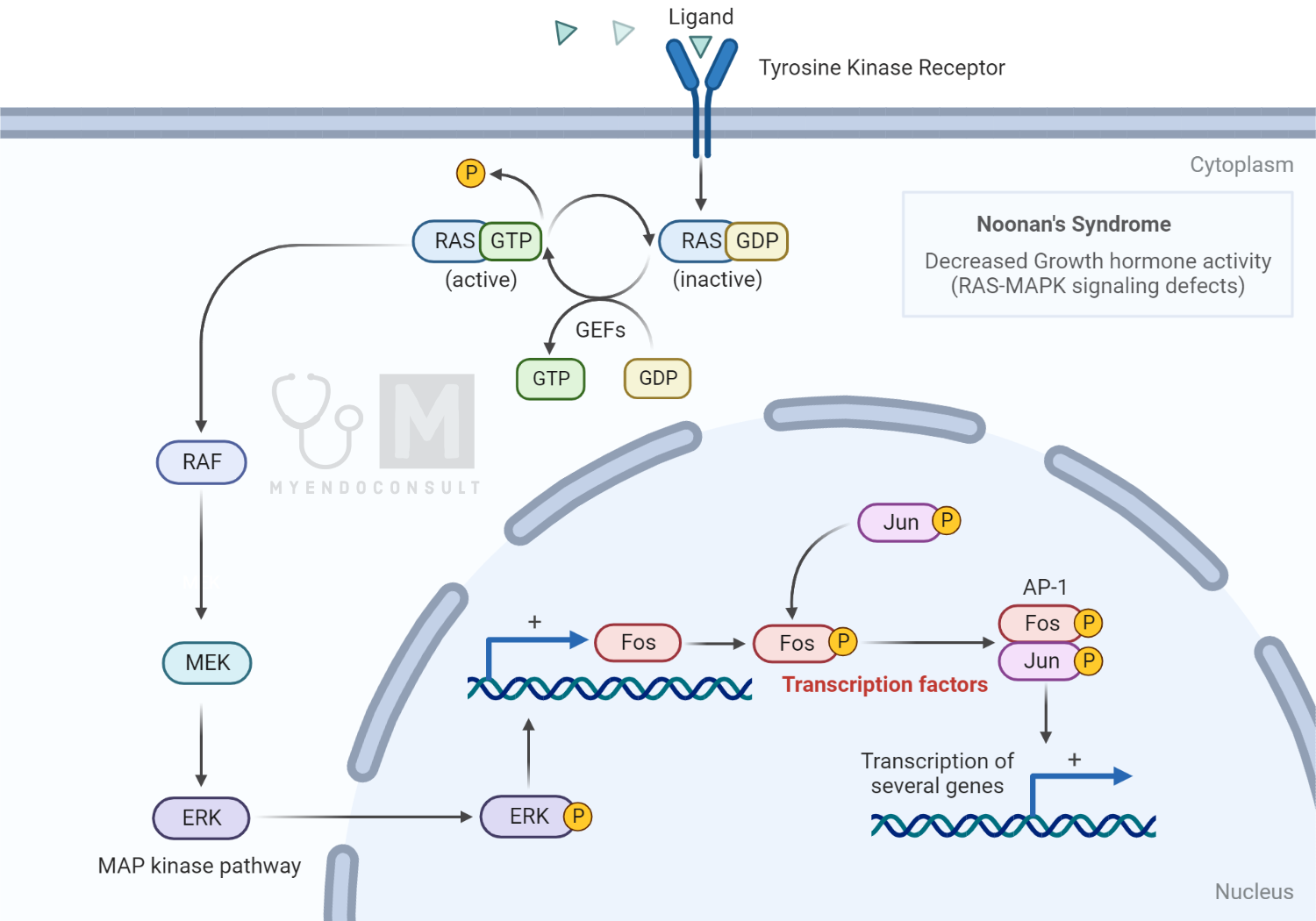

The most common pathologies are GH deficiency, hypothyroidism, celiac disease, Noonan syndrome (a genetic disorder due to mutations in genes in the RAS-MAPK pathway), and Turner syndrome (a genetic disorder due to a missing or abnormal X chromosome)

History and Physical examination

Every medical evaluation starts with a medical history. Additionally, when a child shows a concerning growth pattern, a detailed history of gestational age, birth weight and length, and history of prenatal and perinatal complications, is indicated. A delay in development and poor school performance are indicators too. A history of gastrointestinal system problems and a thorough dietary recall is required to evaluate the adequacy of nutritional intake.

Moreover, we should be aware of the medications that the child takes. Medications such as stimulants used to treat attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anticonvulsants, and antidepressants can affect growth[3].

A complete physical examination successfully indicates signs of systemic illnesses and endocrinopathies, especially any present dysmorphic features, the length of metacarpal bones, body proportions, and puberty staging are significant[3].

Also, we cannot lose sight of the fact that there are normal patterns of short stature in families with a low genetic potential for growth in height.

Accordingly, there is a formula that helps in determining whether a child’s height is consistent with his or her genetic potential. This formula, known as the mid-parental height formula, depends on the sex and is shown below.

Mid Parental Height Formula (Boys)

Boys (father’s height [cm] + mother’s height [cm] + 13) ÷ 2Mid Parental Height Formula (Girls)

Girls (father’s height [cm] + mother’s height [cm] − 13) ÷ 2

For instance, gastrointestinal system diseases like celiac disease or inflammatory bowel disease can cause short stature due to malabsorption. A celiac disease screen is done by measuring the Immunoglobulin A levels, specifically IgA tissue transglutaminase and IgA endomysial antibodies, with an immunofluorescence reaction. On the other hand, complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein levels can indicate inflammatory bowel disease.

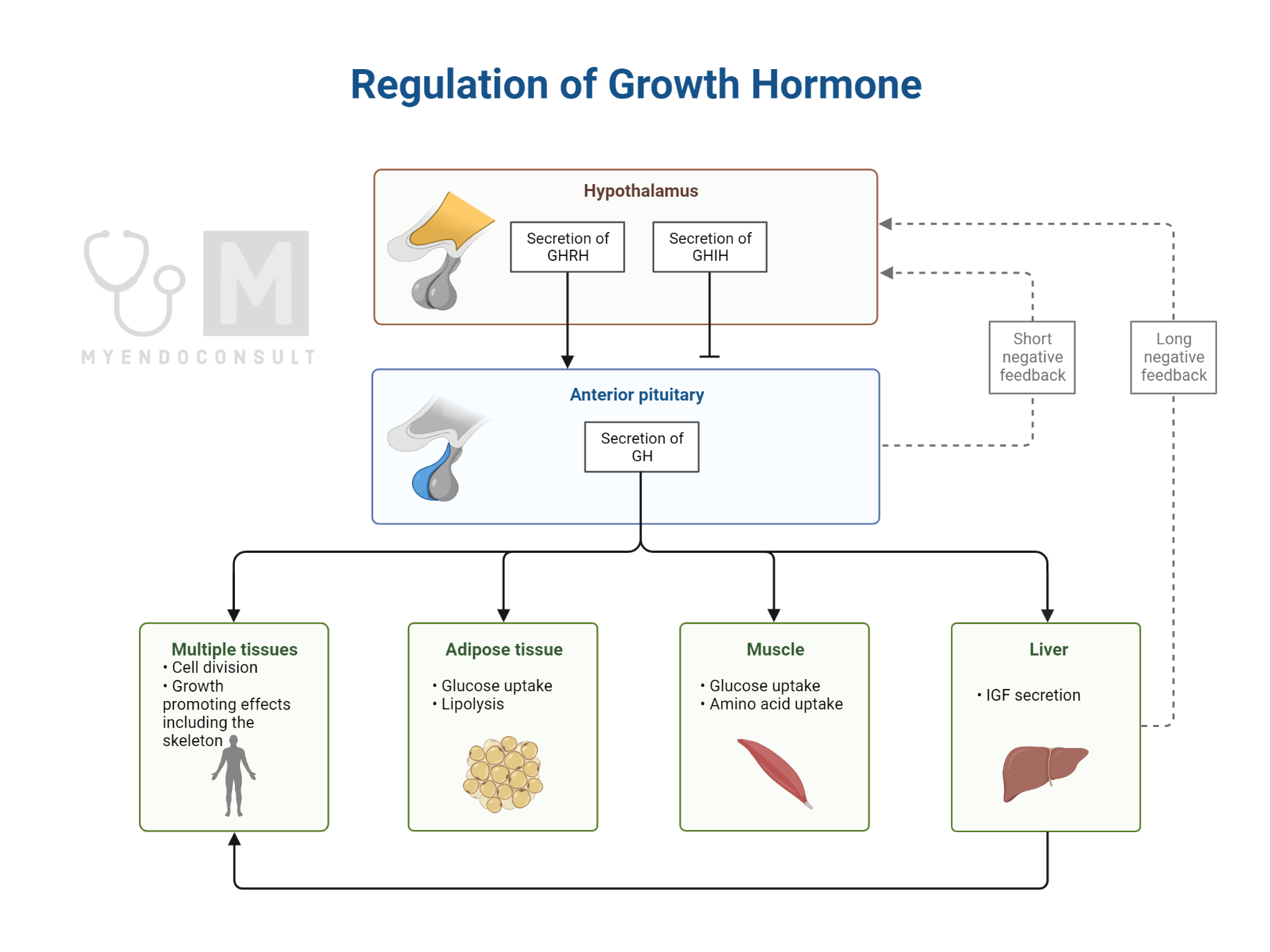

An equally important cause of short stature is hypothyroidism. Accordingly, thyroid function tests have to be ordered. Most importantly, growth hormone levels and insulin-like growth factor 1 or its binding protein should be measured since they are the primary regulators of growth.

The next step is an assessment of skeletal maturity. A plain radiograph of the left hand and wrist is usually sufficient to evaluate this. Skeletal maturity is delayed in conditions such as endocrinopathies, nutritional deficiency, chronic illnesses, and CDGP- constitutional delay in growth and puberty.

Similarly, another important parameter is bone age. Bone age is evaluated with two methods. The first method, the most used in the United States, is the Greulich and Pyle method, which compares the patient’s radiograph with a reference image in an atlas[6].

The other assessment tool is the Tanner-Whitehouse method which applies scores to maturity indicators of the individual bones of the hand and wrist[6]. These methods can help predict adult height, which is significant in considering treatments.

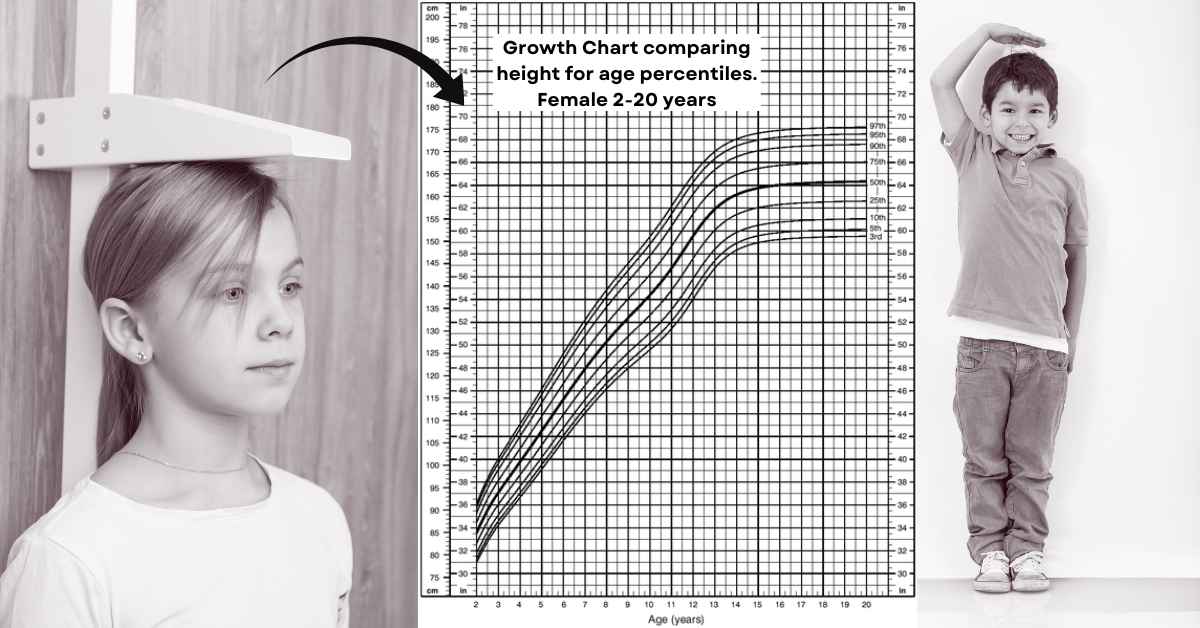

However, infancy and the period of adolescence can show variations in growth. Therefore, Tanner and Davies made longitudinal growth charts that show varieties in growth patterns based on puberty onset. Children who end up at the same adult height may follow different patterns depending on whether they mature at an average age, early or late[3].

During adolescence, an early-maturing child moves to a higher percentile because his/ her growth peak will be earlier than average. In contrast, a late-maturing child moves to a lower percentile as his/her peers start their growth spurts while he/she continues to grow at a prepubertal rate. This is often referred to as a constitutional delay of growth and puberty (CDGP)[4].

Finally, when CDGP and all other diseases that cause this condition are excluded, an individual is diagnosed with Idiopathic Short Stature (ISS)[5].

Investigations (laboratory and Radiologic)

While radiography scans help determine skeletal maturity and the metabolic state of the bones, laboratory screening helps identify the most common pathological causes of short stature.

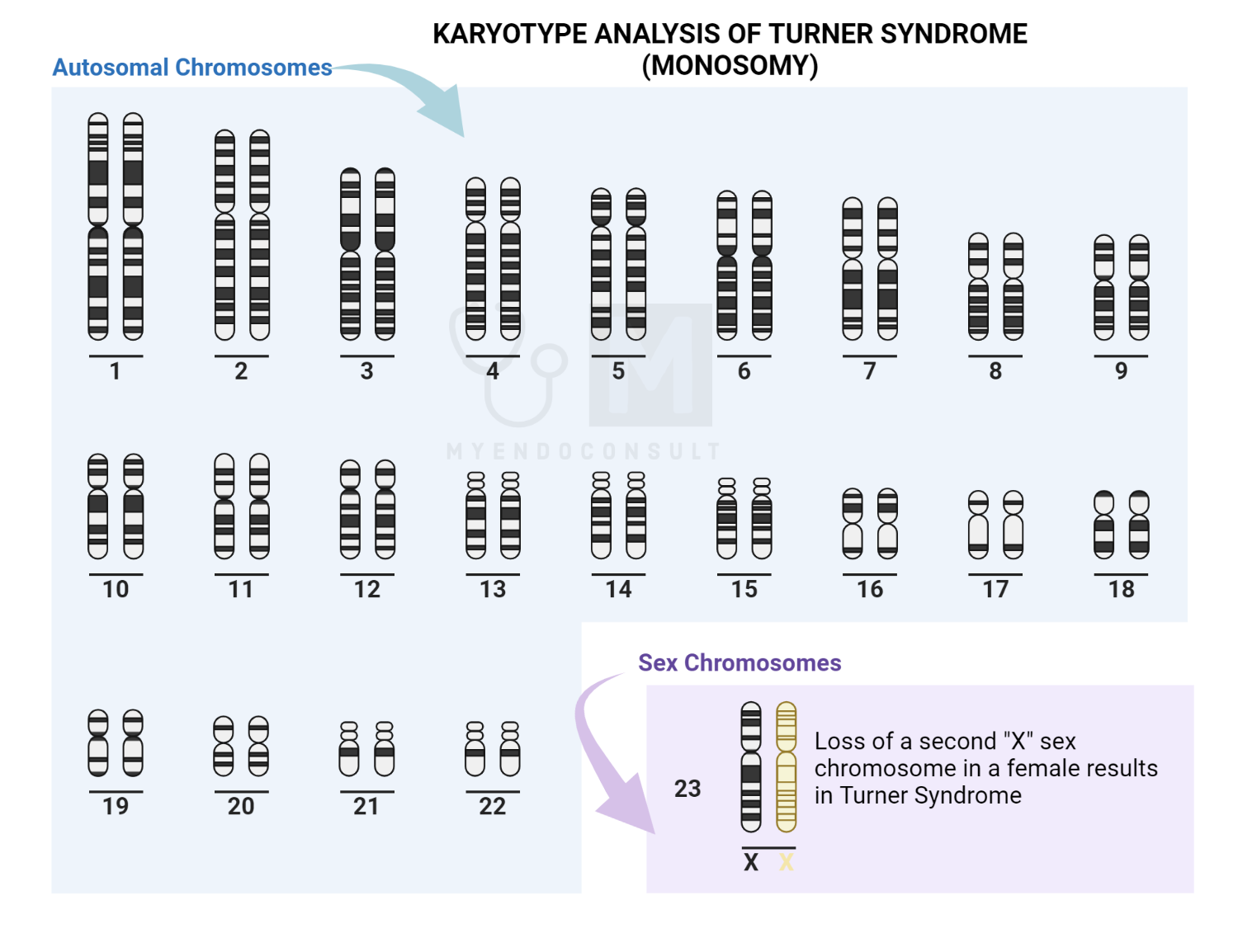

Next, a karyotype should be done if a girl’s short stature is unexplained after initial screening or with typical features of Turner syndrome. Turner syndrome is a genetic disorder due to a missing or abnormal X chromosome[7]. While girls with Turner syndrome typically have physical findings: webbing of the neck, low posterior hairline, short metacarpals, dysplastic nails, higharched palate, and ptosis[8], it is essential to appreciate that short stature may be the only significant sign[3].

Finally, we have to consider gene defects that may exist. For instance, haploinsufficiency of the short stature homeobox-containing (SHOX) gene might be the etiology of short stature in Turner syndrome through loss of normal chondrocyte function at the epiphyseal growth plate [9]. Gene mutations and deletions in the SHOX gene and its enhancer region downstream are also found in children with unexplained idiopathic short stature[9-13].

To summarise, the differential diagnosis of short stature is a broad spectrum that includes: genetic short stature, skeletal dysplasias, teratogenic effects of radiation received while in utero, genetic or chromosomal abnormalities such as Turner syndrome, nutritional deficiencies, and malabsorption due to chronic bowel diseases, dysfunctions of the endocrine system, growth hormone deficiency, hypothyroidism, glucocorticoid excess amongst others.

Treatment (management)

Although short stature may be a sign of underlying pathology, short stature itself is not a disease. However, it is considered more of a social problem because it is perceived as a disability[14]. The first option for the treatment of short stature is growth hormone therapy. Short-term risks associated with growth hormone therapy include insulin resistance (with increased incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus in children with other risk factors), cerebral pseudotumor, and slipped capital femoral epiphyses[15].

Additionally, there are long-term risks, such as the potential correlation between cancer risk and IGF-1 levels observed in nested case-control trials[16]. This possibility is highlighted by results from SAGhE (Safety and Appropriateness of Growth Hormone Treatments in Europe), but the data are conflicting and controversial [18-19].

Eventually, Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists can be used to slow pubertal progression, allowing a more extended period of growth, but the increase in adult height is often clinically insignificant[20].

Another option is using aromatase inhibitors since estrogen mediates skeletal maturation and epiphyseal fusion of the bones in both sexes. Although these agents do not delay pubertal development, they are still considered experimental [21-22].

Lastly, oxandrolone (a nonaromatizable anabolic steroid with a high anabolic-to-androgenic ratio) might be used to stimulate growth in boys with CDGP. The mechanism of action on growth is unclear, but it may increase growth hormone–IGF-1 axis activity and may have effects on the estrogen receptor[22].

Conclusion

To conclude, short stature itself is not a disease, but it is considered a problem, especially because it might be a sign of an underlying disease. Short stature can be normal in families with low potential for growth, or it can be secondary to endocrine dysfunctions, chronic gastrointestinal diseases, or genetic or chromosomal abnormalities.

Firstly a medical history is taken, and a physical examination is done. Next are the laboratory and genetic tests, as well as radiologic investigations. The treatment available is growth hormone therapy and some other less-used medications due to their clinical insignificance.

References

- 1. Tanner JM, Davies PS. Clinical longitudinal standards for height and height velocity for North American children. J Pediatr. 1985;107(3):317-329

- 2. R.G Rosenfeld, Molecular mechanisms of IGF-I deficiency, Horm. Res 65 (Suppl.1) (2006) 15-20.

- 3. Rose SR, Vogiatzi MG, Copeland KC. A general pediatric approach to evaluating a short child. Pediatr Rev. 2005;26(11):410-420.

- 4. Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH, Takaishi M. Standards from birth to maturity for height, weight, height velocity, and weight velocity: British children, 1965. Arch Dis Child. 1966;41(219): 454-471

- 5. Ranke MB. Chairman’s summary: definition of idiopathic short stature. Horm Res Paediatr. 2011;76(suppl 3):2.

- 6. Martin DD, Wit JM, Hochberg Z, et al. The use of bone age in clinical practice—part 1. Horm Res Paediatr. 2011;76(1):1-9.

- 7. Sisley S, Trujillo MV, Khoury J, Backeljauw P. Low incidence of pathology detection and high cost of screening in the evaluation of asymptomatic short children. J Pediatr. 2013;163(4):1045-1051

- 8. Saenger P. Turner syndrome. In: Sperling MA, ed. Pediatric Endocrinology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2008:610-661.

- 9. Binder G. Short stature due to SHOX deficiency: genotype, phenotype, and therapy. Horm Res Paediatr. 2011;75(2):81-89.

- 10. Rosilio M, Huber-Lequesne C, Sapin H, Carel JC, Blum WF, Cormier-Daire V. Genotypes and phenotypes of children with SHOX deficiency in France. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(7):1257- 1265

- 11. Benito-Sanz S, Aza-Carmona M, Rodríguez-Estevez A, et al. Identification of the first PAR1 deletion encompassing upstream SHOX enhancers in a family with idiopathic short stature. Eur J Hum Genet. 2012;20(1):125-127.

- 12. Hardin DS. Treatment of short stature and growth hormone deficiency in children with somatotropin (rDNA origin). Biologics. 2008;2(4):655-661.

- 13. De Sanctis V, Tosetto I, Iughetti L, et al. The SHOX gene and the short stature: roundtable on diagnosis and treatment of short stature due to SHOX haploinsufficiency: how genetics, radiology, and anthropometry can help the pediatrician in the diagnostic process Padova (April 20th, 2011). Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2012;9(4):727-733.

- 14. Allen DB. Growth hormone therapy for short stature: is the benefit worth the burden? Pediatrics. 2006;118(1):343-348.

- 15. Carel JC, Butler G. Safety of recombinant human growth hormone. Endocr Dev. 2010;18:40-54.

- 16. Rosenfeld RG, Cohen P, Robison LL, et al. Long-term surveillance of growth hormone therapy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(1):68-72.

- 17. Carel JC, Ecosse E, Landier F, et al. Long-term mortality after recombinant growth hormone treatment for isolated growth hormone deficiency or childhood short stature: preliminary report of the French SAGhE study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(2):416-425.

- 18. Sävendahl L, Maes M, Albertsson-Wikland K, et al. Long-term mortality and causes of death in isolated GHD, ISS, and SGA patients treated with recombinant growth hormone during childhood in Belgium, the Netherlands, and Sweden: preliminary report of 3 countries participating in the EU SAGhE study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(2):213-217.

- 19. Palmert MR, Dunkel L. Clinical practice: delayed puberty. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(5): 443-453.

- 20. Carel JC. Management of short stature with GnRH agonist and co-treatment with growth hormone is controversial. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2006;254-255:226-233.

- 21. Geffner ME. Aromatase inhibitors to augment height: continued caution and study required. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2009;1(6):256-261.

- 22. Dunkel L. Treatment of idiopathic short stature: effects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogs, aromatase inhibitors, and anabolic steroids. Horm Res Paediatr. 2011;76(suppl 3):27-29.

Kindly Let Us Know If This Was helpful? Thank You!