Mediterranean Diet Pyramid

The Mediterranean diet is based on the eating, lifestyle, agricultural, and cultural habits of the countries around the Mediterranean basin and was first described as being low in saturated fats and high in vegetable oils.1 Current definitions of the diet vary across the world and include varying descriptions of food groups and quantity of intake; as such, they are referred to as Mediterranean-style diets.1-3 Nonetheless, this diet remains a primarily plant-based composition.4 The Mediterranean diet is known to confer a wide range of health benefits that minimize the risk of non-communicable diseases, including obesity, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and cognitive disorders such as dementia.3-5 In addition, it has been associated with a positive environmental impact, making it a favorable lifestyle habit.3,4,6 Its advantages in preventing diabetes and positive effects on weight loss, glycemic control, and cardiovascular risk factors have made it an area of interest in diabetes research.5,6

Its role in controlling glycemia is attributed to the effects on postprandial and fasting glucose levels, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and insulin sensitivity, with many publications reporting great efficacy in improving glycemic control.2,5

Diabetes mellitus comprises a group of chronic metabolic diseases whose primary pathology is chronic hyperglycemia. It encompasses type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, and gestational diabetes, among other less common forms.7 Diabetes has been on the global rise in recent decades due to increased industrialization, widespread dissemination of Western eating patterns, physical inactivity, and increasing incidence of obesity and metabolic syndrome.5 The worldwide prevalence of diabetes was estimated at 424.9 million diagnosed cases in individuals aged 20–79 years (8.8%) in 20178,9 and 536.6 million (10.5%) in 2021.10

Low Carb Diet in Diabetes

Carbohydrates, which constitute over 50% of daily caloric intake in the general population, are dietary macronutrients and the primary source of energy for the body, producing the greatest effect on blood sugar levels after meals.

In the United States, 30.2 million people aged 20-79 years were reported to have diabetes in 2017.8 Although the prevalence is higher in urban regions and high-income countries,10 an upward trend is reported in rural areas and low-income countries due to rapid urbanization and changes in lifestyle behaviors such as increased consumption of processed foods and sedentary behavior.8 Type 2 diabetes is the most common form of the disease in adults, accounting for over 90% of cases worldwide,6 although the true prevalence is unknown as many people remain undiagnosed.8 The increasing prevalence of diabetes makes it a significant public health problem worldwide in terms of disease burden, health expenditures, and all-risk mortality.

The management of diabetes encompasses both pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches; the latter includes dietary interventions, increased physical activity, cessation of smoking, and limited alcohol consumption.

The association between diet and diabetes has been studied in relation to its role in the pathogenesis, progression, and prevention of the disease.11,12 Dietary factors have been linked to weight gain, pro-inflammatory conditions, and alterations in gut microbiota, all of which are implicated in the progression of diabetes.13 Increased consumption of red and processed meat, refined and sugary carbohydrates, and inadequate intake of plant-based foods (legumes, whole grains, vegetables, and fruits) are strongly linked to type 2 diabetes as this leads to increased weight and adiposity and decreased amounts of protective nutrients.12 Overweight and obesity are established major risk factors for type 2 diabetes due to their negative impacts on the body’s lipid profile and insulin resistance.12 In type 1 diabetes, dietary factors can be implicated in its pathogenesis by contributing to β-cell autoimmune destruction.14,15

For instance, early and excessive exposure to cow’s milk protein and early introduction of gluten-containing solid foods in children have been associated with β-cell autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes, although research findings are inconsistent.14 In contrast, vitamin D may have a protective role in the development of β-cell autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes.14,15 Thus, dietary changes, which consist of healthy eating and substitution/limitation of foods associated with increased diabetes risk, are of great public health importance in preventing and managing diabetes.

The aim of this article is to discuss the potential benefits of Mediterranean diets in improving glycemic control in diabetes, providing an overview of the current knowledge on the associations between Mediterranean diets and glycemic control and a summary of other health benefits.

The Mediterranean Diet

The Mediterranean diet, considered a collection of dietary, cultural, and lifestyle habits traditionally followed by countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea, is one of the most researched16 and has been acknowledged as one of the most healthy dietary patterns in the world.4

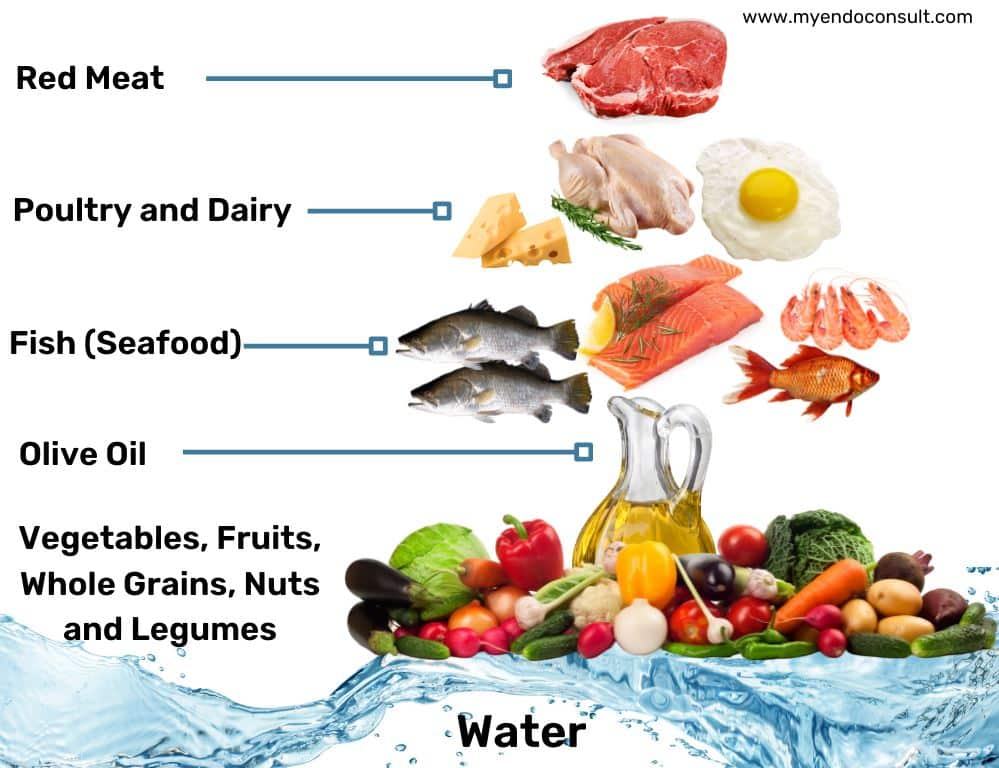

It is largely a plant-based, nutrient-dense diet characterized by abundant consumption of seasonal vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts and seeds, and olive oil as the main source of fat.4-6 Other components of the diet are water as the main beverage and low to moderate quantities of fish, eggs, poultry, and dairy products (mainly yogurt and cheese).4,5,17 Wine is consumed in low-to-moderate quantities with meals and is the main source of alcohol.4,17 It also integrates extremely moderate consumption of red and processed meat and sugar-sweetened foods and beverages.4,6

The recommended number of servings and food proportions in the Mediterranean diet are guided by the Mediterranean pyramid.1,18

In regard to macronutrient quantity, Mediterranean-style diets can vary; they may be a low-carbohydrate Mediterranean diet, in which monounsaturated fats provide the most caloric intake, or a high-carbohydrate Mediterranean diet, with carbohydrates providing most (50–55%) of the caloric intake.19,20 Other than dietary aspects, the Mediterranean model also emphasizes environmentally friendly agricultural and cultural practices, regular physical and social activity, and adequate rest, making it more of a lifestyle than simply an eating pattern.3,18

The nutritional aspect of this diet is described as low in saturated fats and animal protein; high in antioxidants, vitamins, minerals, fibers, probiotics, phytosterols, polyphenols, and mono- and poly-unsaturated fats; and balanced in omega-3/omega-6 fatty acids.6,21 Its health benefits have been attributed to these nutritional qualities, obtained from key components of the diet.16,21

Vegetables are an important source of phenolic compounds,21 which are thought to have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects.22

Additionally, vegetables have abundant nutrients including fiber, potassium, vitamins A, C, K and E, copper, magnesium, folate, etc.21 Nutrients are also plenty in fruits, legumes, whole grains, and nuts. Olive oil, a fundamental element of the Mediterranean diet, is a major source of mono- and poly-unsaturated fats, polyphenols, and phytosterols.21,22 Fish is also a source of healthy fats,13 mainly, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids.21,23 Thus, the various food groups of the Mediterranean diet provide synergistic health effects due to high intake of protective bioactive components mentioned above.4,16,21 Furthermore, reduced consumption of less healthy foods such as animal and processed foods high in saturated and trans fats and low alcohol intake is beneficial for health.13 Moderate consumption of red wine with meals has been linked to a lowered risk of some features of metabolic syndrome.23,24

In contrast to the Mediterranean diet, the standard Western diet has been linked to poor health outcomes including cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, and cancer.12,13,25 Western dietary patterns largely consist of highly processed foods, including refined grains, processed and red meats, sweetened and salty foods, fried foods, and high-fat dairy products, whereas the intake of fruits and vegetables is low.13

For this reason, Western diets are calorie-dense and contain high amounts of saturated fats, trans fats, sugars, salt, and animal protein, all of which have been associated with adverse health outcomes.12,13

Furthermore, they are low in healthy fats such as omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, fibers, micronutrients, phytochemicals, and antioxidants.13

This is in contrast to the Mediterranean diet, which is very low in processed and animal foods and high in plant-based foods and is hence a nutritionally balanced eating model that is low in unhealthy fats, salt, and sugars.13 The Mediterranean diet is also higher in seafood quantity, a source of healthy fats, compared to the Western diet.13

Additionally, the Mediterranean diet has a beneficial impact on the environment as it is mainly plant-based with low demands on soil, water, and energy resources, contrasting the Western dietary pattern which is animal-based and thus has a higher environmental footprint.3,26

Mediterranean diets and glycemic control

The benefits of Mediterranean diets in diabetes prevention and management have been studied widely, mainly for type 2 diabetes. Evidence demonstrating its role in type 1 diabetes is scarce, although beneficial cardiometabolic outcomes27 and improved quality of life28 have been reported. The Mediterranean diet promotes glycemic control due to the nutritional quality of the diet which offers protective biologically active ingredients including antioxidants, vitamins, minerals, fibers, phytosterols, polyphenols, and mono- and poly-unsaturated fatty acids.4,16,21 Mediterranean diets have been shown to improve glycemic control through changes in postprandial and fasting glucose levels, HbA1c, and insulin sensitivity.2,5,29 They decrease insulin resistance as a result of changes in weight and adiposity linked to foods low in saturated fats and high in monounsaturated fatty acids.6,16,17,19,30 Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant compounds (e.g., vitamin E and C, β-carotene, polyphenols such as flavonoids, and minerals such as selenium) also play a role in improving insulin sensitivity by mitigating the effects of inflammation and oxidative stress on pancreatic β cells and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake.5,17,29,31 Better insulin sensitivity subsequently improves glucose utilization and homeostasis.19 In addition, the presence of fiber-rich foods in the diet helps control glycemia as fibers delay gastric emptying and lower the gastric index of carbohydrate-rich foods.21 The use of the Mediterranean diet as a dietary intervention for glycemic control is supported by the American Diabetes Association and American Heart Association based on available evidence.32-34

Many studies have demonstrated the efficacy of adherence to a Mediterranean-style diet in glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes,2,3,5,19,21,35-39 lowering HbA1c levels up to 0.3–0.47%.38 Many of these studies demonstrate the superiority of Mediterranean diets in improving glycemic control. In a four-year randomized controlled clinical trial by Esposito et al.,35 Mediterranean diets showed significantly lower HbA1c and fasting glucose levels when highly adhered to by diabetic patients. A study comparing a low-fat diet to the Mediterranean diet showed a substantial decrease in HbA1c after six months.36 Elhayany et al.,19 found a significant reduction in HbA1c in those following a low-carbohydrate Mediterranean diet in a 12-month randomized controlled clinical trial. A meta-analysis by Ajala et al.,39 evaluated the effects of various diets on the nutritional management of type 2 diabetes and found a significant reduction in HbA1c with the Mediterranean diet. A systematic review of eight metanalyses and five randomized controlled trials examined the effect of the Mediterranean diet on the treatment of diabetes and prediabetic states and reported lower HbA1c levels in patients who adhered to the Mediterranean diet.38

Reducing fasting or postprandial glucose levels is another means by which the Mediterranean diet benefits glycemic control, as demonstrated by these studies.2,19,30,35,40 A meta-analysis of nine randomized controlled trials observed lowered fasting glucose levels in patients with type 2 diabetes.2 Estruch et al.,40 observed lower levels of fasting glucose after three months in those following the Mediterranean diet compared to a low-fat diet. Another study showed low fasting glucose levels as well as low HbA1c in the Mediterranean diet control group.30 A study assessing a key component of the Mediterranean diet, virgin olive oil, showed lowered fasting glucose in individuals with overweight and type 2 diabetes taking regular and moderate amounts of virgin olive oil for eight weeks.41

Not many studies have assessed the effects of the Mediterranean diet on insulin resistance in patients with diabetes, but studies have demonstrated improved insulin sensitivity with diets rich in monounsaturated fats, anti-inflammatory nutrients, and antioxidant compounds.16,17,19,29-31 The polyphenolic compound oleuropein, found in virgin olive oil and olive leaf extracts, has shown improvements in insulin sensitivity, as well as β-cell function.16,42 A meta-analysis by Huo et al.,2 demonstrated changes in fasting insulin levels in individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Implementing a Mediterranean diet

Greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet is known to provide more benefits than low adherence.35 This eating pattern can be implemented by encouraging the gradual incorporation of healthier dietary options such as increased intake of vegetables and fruits and lower consumption of refined and processed foods.20 The individual’s personal and cultural preferences, access to foods, socioeconomic status, willingness to change eating habits, and cardiometabolic status require consideration before implementing a suitable dietary intervention.34 For people with diabetes, it is important to emphasize high-quality foods (e.g., wholegrain rather than refined carbohydrates, mono- and polyunsaturated fats rather than saturated animal fats) and lower total energy intake, standards that the Mediterranean diet meets.31,43

The Mediterranean pyramid can guide the variety, proportionality, and moderation of foods and beverages in the diet (see the featured infographic).18

Individuals can commence a Mediterranean diet by incorporating one or more of the following options into their eating habits18,43:

- Increasing vegetable intake, including tomatoes, broccoli, kale, spinach, onions, cauliflower, carrots, cucumbers, etc., with up to three to five servings daily

- Consuming fruits daily, such as apples, bananas, oranges, and grapes as desserts or snacks

- Increasing the use of olive oil, which is high in monounsaturated fatty acids, to replace butters and margarines, which are high in saturated and trans fatty acids

- Limiting intake of refined, processed, and sweetened foods and alcohol consumption

- Limiting processed and red meat and substituting it with fish/seafood (e.g., salmon, sardines, trout, tuna, shrimp, and crab) and poultry, which are consumed at least twice weekly

- Eating nuts or seeds like almonds, walnuts, cashews, sunflower seeds, and pumpkin seeds as daily snacks

- Daily intake of wholegrain breads, rice, pasta, and cereals

- Consuming daily low-fat or non-fat dairy products, mainly cheeses, and yogurt

- Obtaining protein from foods such as poultry, fish, legumes (e.g., lentils, beans, and chickpeas), nuts, and other plant-based sources

- Using herbs and spices instead of salt

- Drinking water as the main beverage and moderate amounts of red wine with meals.

Specific areas suggested for initial dietary changes may include reducing the number of weekly meals that incorporate red meat by substituting with legumes, poultry, or fish; increasing the intake of fruits and vegetables; and replacing saturated and trans fats with monounsaturated fats.20 Examples of Mediterranean-style meals include 1 cup of cooked oats mixed with 2 tablespoons chopped walnuts, ¾ cup of fresh or frozen blueberries, and a sprinkle of cinnamon for breakfast; ¼ cup of nuts for a snack; 1 cup of beans and 1 cup of rice with two cups of fresh salad and olive dressing for lunch; 1-2 fruits or a cup of fruit salad for a snack; and baked salmon, 1 medium baked sweet potato, and 1 cup of chopped steamed cauliflower for dinner, with a fresh green salad and olive dressing.44 Other examples of Mediterranean meals can be found here: 7-day Mediterranean healthy meal plan - Diabetes Canada; Mediterranean Diet (va.gov); PEN_handout-1500-kcal-Med-Diet-Meal-Plan.pdf (ubc.ca).

Making changes in dietary habits can be challenging for many people. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offers general advice on steps to begin and maintain healthful dietary changes.45 Consideration of all current eating habits and triggers for unhealthy eating (e.g., stress, boredom, or other emotional states) should be made to ensure appropriate changes; when recognized, unhealthy eating patterns and triggers should be replaced with healthier options and habits; changes should be gradual and patience should be exercised to maintain the healthy eating habits.45 Factors that deter from healthy eating, such as lack of education, income, and eating disorders, should be identified and addressed.46

Gradual dietary changes are easier to follow and maintain; nutritional guidelines recommend boosting daily fruit and vegetable intake, minimizing consumption of refined carbohydrates by choosing whole grains and legumes, limiting the intake of red meat and sugars, choosing foods rich in unsaturated fats such as fish and vegetable oils, eating moderate amounts of low-fat dairy products, and consuming more water and less alcohol.

This is a consensus in several nutritional guidelines, developed in various countries to help the population gain adequate evidence-based knowledge to make healthy changes in their diet.47-51

Choosing a variety of high-quality foods from all food groups (vegetables and fruits, starches, dairy, protein, and fat) in appropriate proportions for a meal is another way to change dietary patterns.48

The Plate Method is a way to incorporate a variety of food groups into meals; half the plate should include non-starchy vegetables, a quarter of starchy foods, and a quarter of lean meats and plant-based protein foods, with water, moderate low/no-fat dairy products, and fruit on the side of the plate.52,53

Adherence to healthier diets can be promoted when nutritional guidance from experts and social support is given.46,54

Additionally, combining dietary interventions with increased physical activity improves adherence to dietary changes.46 Other factors that influence changes in eating habits include self-image, personal health, sociodemographic factors (e.g., access to healthy food, education, income), and willingness and ability to change.46

Other benefits of Mediterranean diets

Long-term adherence to the Mediterranean diet has shown favorable effects in preventing and managing non-communicable diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and cognitive decline, and lowering all-risk mortality.3-5,23,55 Some proposed mechanisms by which the Mediterranean diet confers health benefits, such as anti-inflammatory and antioxidative properties of polyphenols, are common to different pathological conditions, whereas others are disease-specific.4 In addition, moderate consumption of alcohol and physical activity, which are elements of the Mediterranean lifestyle, are protective against many non-communicable diseases.

Obesity and Metabolic syndrome

The metabolic syndrome is a collection of common cardiovascular disease mediators, including obesity, hyperglycemia, low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, hypertension, and elevated triglycerides and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol.56 The Mediterranean diet may increase the potential for remission and reduce the risk of metabolic syndrome.38,57,58 Loss of weight and central adiposity brought on by adherence to the Mediterranean diet can explain this benefit.4 The Mediterranean diet aids in reducing the risk of obesity and overweight, an outcome attributed to a higher intake of fiber-rich foods, water, and monounsaturated fats, and lower meat and sugar consumption.31,55,59 It is thus low in energy density, glycemic load, and cholesterol‑raising fats, high in water content, and promotes satiety, thereby preventing weight gain, obesity, and dyslipidemia (elevated levels of LDL cholesterol, total cholesterol, and triglycerides and low HDL cholesterol).60

Cardiovascular disease

Cardiovascular diseases are a major cause of mortality worldwide21 and diet plays an important role in mitigating or exacerbating the risks. For example, a diet high in saturated and trans fatty acids has been linked to dyslipidemia, an important risk factor for cardiovascular diseases such as atherosclerosis.21,61 The Mediterranean diet, which is rich in monounsaturated fatty acids, has been shown to reduce total and LDL cholesterol and triglyceride levels, thus minimizing cardiovascular risk factors.17,19,21,30,38 It is also thought to confer cardiovascular benefits through anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects on the vascular wall.21 Improvements in blood pressure have also been reported.2,17,62

Cancer

Diet plays an essential role in the prevention of certain cancers. High intake of vegetables, legumes, fruit, whole grains, fish, and low-fat dairy products, with moderate consumption of alcohol and limited intake of red and processed meats, sugar-sweetened foods, and saturated and trans fats has been linked to reduced cancer risk.4,63 High amounts of dietary fiber, present in several plant foods, reduce the risk of colorectal cancer.4,63 Greater adherence to the Mediterranean diet has been associated with a significantly lower risk of certain cancer types such as colorectal, liver, head and neck, and prostate cancer and overall cancer mortality.63-65

Cognitive disorders

Cognitive decline is generally the result of the interplay between genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors, including diet. The Mediterranean diet is one of the eating patterns demonstrated to have protective effects on cognitive function, minimizing the risk of age-related cognitive decline and cognitive disorders such as dementia. 4,66 It is full of biologically active components with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties which are thought to be neuroprotective.4,16,66 Moreover, the Mediterranean dietary model emphasizes regular physical and social activity and adequate rest, which have a compounding effect on delaying cognitive decline.3,4,18

Conclusion

Mediterranean diets have been shown to improve glycemic control through favorable effects on postprandial and fasting glucose levels, glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), and insulin sensitivity. The intake of high dietary monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids, fibers, antioxidants, and anti-inflammatory foods and lower consumption of processed and refined foods rich in saturated and trans fatty acids has shown improvements in glycemic control (insulin resistance, HbA1c, and fasting blood glucose). It is acknowledged by health regulatory bodies as a suitable nutritional intervention for controlling glycemia in people with type 2 diabetes.

The Mediterranean diet offers extensive nutritional benefits that improve health outcomes, including a risk reduction in the incidence of obesity, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and cognitive decline. It is described in a way that is easy to follow and modify based on locally-available foods; food groups, rather than nutritional content, are emphasized, and servings are clearly highlighted. The Mediterranean diet includes the use of olive oil, herbs, and spices for cooking, making meals palatable and easier to adhere to. It does not eliminate foods but enforces limitations on those that are less healthy; therefore, it does not promote major changes. Moreover, it encourages the consumption of nutrient-dense foods, low alcohol intake, social activity, exercise, and adequate sleep, which provide synergistic benefits for good health. Furthermore, it is an environmentally-friendly practice with minimal impact on resources. These qualities make the Mediterranean diet a remarkable lifestyle as it encourages healthy dietary, behavioral, as well as agricultural practices.

References

- 1.Davis C, Bryan J, Hodgson J, Murphy K. Definition of the Mediterranean Diet: A Literature Review. Nutrients. 2015; 7.

- 2.Huo R, Du T, Xu Y, Xu W, Chen X, Sun K, et al. Effects of Mediterranean-style diet on glycemic control, weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors among type 2 diabetes individuals: a meta-analysis. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2014.

- 3.Guasch-Ferre M, Willett W. The Mediterranean diet and health: a comprehensive overview. Journal of Internal Medicine. 2021; 290(3).

- 4.Dominguez LJ, Bella GD, Veronese N, Barbagallo M. Impact of Mediterranean Diet on Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases and Longevity. Nutrients. 2021; 13.

- 5.Sleiman D, Al-Badri MR, Azar ST. Effect of Mediterranean diet in diabetes control and cardiovascular risk modification: a systematic review. Front Public Health. 2015; 3(69).

- 6.Milenkovic T, Bozhinovska N, Macut D, Bjekic-Macut J, Rahelic D, Asimi ZV, et al. Mediterranean Diet and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Perpetual Inspiration for the Scientific World. A Review. Nutrients. 2021; 13.

- 7.Petersmann A, Nauck M, Müller-Wieland D, Kerner W, Müller UA, Landgraf R, et al. Definition, Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes Mellitus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2018; 126.

- 8.Lovic D, Piperidou A, Zografou I, Grassos H, Pittaras A, Manolis A. The Growing Epidemic of Diabetes Mellitus. Current Vascular Pharmacology. 2018; 18.

- 9.Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, Huang Y, Fernandes JD, Ohlrogge AW, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018; 138.

- 10.Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022; 183.

- 11.Mann JI, Morenga LT. Diet and diabetes revisited, yet again. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013; 97.

- 12.Tinajero MG, Malik VS. An Update on the Epidemiology of Type 2 Diabetes: A Global Perspective. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2021; 50(3).

- 13.Guilleminault L, Williams EJ, Scott HA, Jensen M, Wood LG. Diet and Asthma: Is It Time to Adapt Our Message? Nutrients. 2017; 9.

- 14.Nielsen DS, Krych Ł, Buschard K, Hansen CH, Hansen AK. Beyond genetics. Influence of dietary factors and gut microbiota on type 1 diabetes. FEBS Letters. 2014; 588(22).

- 15.Virtanen SM. Dietary factors in the development of type 1 diabetes. Pediatric Diabetes. 2016; 17(Suppl. 22).

- 16.Kiani AK, Medori MC, Bonetti G, Aquilanti B, Velluti V, Matera G, et al. Modern vision of the Mediterranean diet. J Prev Med Hyg. 2022; 63(Suppl. 3).

- 17.Georgoulis M, Kontogianni MD, Yiannakouris N. Mediterranean Diet and Diabetes: Prevention and Treatment. Nutrients. 2014; 6.

- 18.Fundación Dieta Mediterránea. The Mediterranean Pyramid. [Online]; 2010 [cited 2023 March 21] Available from: https://dietamediterranea.com/nutricion-saludable-ejercicio-fisico/

- 19.Elhayany A, Lustma A, RA, Attal-Singer J, Vinker S. A low carbohydrate Mediterranean diet improves cardiovascular risk factors and diabetes control among overweight patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 1-year prospective randomized intervention study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010; 12(3).

- 20.Benson G, Pereira RF, Boucher JL. Rationale for the Use of a Mediterranean Diet in Diabetes Management. Diabetes Spectrum. 2011; 24(1).

- 21.Schwingshackl L, Morze J, Hoffmann e. Mediterranean diet and health status: Active ingredients and pharmacological mechanisms. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2019 June; 117(6).

- 22.Martín-Peláez S, Fito M, Castaner O. Mediterranean Diet Effects on Type 2 Diabetes Prevention, Disease Progression, and Related Mechanisms. A Review. Nutrients. 2020 July; 12.

- 23.Finicelli M, Salle AD, Galderisi U, Peluso G. The Mediterranean Diet: An Update of the Clinical Trials. Nutrients. 2022 July; 14(14).

- 24.Castaldo L, Narváez A, Izzo L, Graziani G, Gaspari A, Minno GD, et al. Red Wine Consumption and Cardiovascular Health. Molecules. 2019 October; 24(19).

- 25.Cordain L, S Boyd Eaton , Sebastian A, Mann N, Lindeberg S, Watkins BA, et al. Origins and evolution of the Western diet: Health implications for the 21st century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 February ; 81(2).

- 26.Sáez-Almendros S, Obrador B, Bach-Faig A, Serra-Majem L. Environmental footprints of Mediterranean versus Western dietary patterns: beyond the health benefits of the Mediterranean diet. Environmental Health. 2013; 12(Article number: 118).

- 27.Gingras V, Leroux C, Desjardins K, Savard V, Lemieux S, Rabasa-Lhoret R, et al. Association between Cardiometabolic Profile and Dietary Characteristics among Adults with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2015 December ; 115(12).

- 28.Granado-Casas M, Martin M, Martínez-Alonso M, Alcubierre N, Hernández M, Alonso N, et al. The Mediterranean Diet is Associated with an Improved Quality of Life in Adults with Type 1 Diabetes. Nutrients. 2020 January; 12(1).

- 29.Esposito K, Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, Panagiotakos DB, Giugliano D. Mediterranean diet for type 2 diabetes: cardiometabolic benefits. Endocrine. 2016 July; 56(1).

- 30.Esposito K, Maiorino MI, Ciotola M, Palo CD, Scognamiglio P, Gicchino M, et al. Effects of a Mediterranean-Style Diet on the Need for Antihyperglycemic Drug Therapy in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Type 2 Diabetes: A Randomized Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009 September; 151.

- 31.Schrfder H. Protective mechanisms of the Mediterranean diet in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry. 2007; 18.

- 32.Evert AB, Boucher JL, Cypress M, Dunbar SA, Franz MJ, Mayer-Davis EJ, et al. Nutrition Therapy Recommendations for the Management of Adults With Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2014; 37.

- 33.Fox CS, Golden SH, Anderson C, Bray GA, Burke LE, Boer IHd, et al. Update on Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Light of Recent Evidence: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2015; 38(9).

- 34.American Diabetes Association. 4. Lifestyle Management: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care. 2018 Jan; 41(Suppl 1).

- 35.Esposito K, Maiorino M, Palo CD, Giugliano D. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet and glycaemic control in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med. 2009; 26.

- 36.Toobert DJ, Glasgow RE, Strycker LA, Jr MB, Radcliffe JL, Wander RC, et al. Biologic and quality-of-life outcomes from the Mediterranean Lifestyle Program: a randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care. 2003; 26(8).

- 37.Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, Shahar DR, Witkow S, Greenberg I, et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med. 2008 ; 359(3).

- 38.Esposito K, Maiorino M, Bellastella G, Chiodini P, Panagiotakos D, Giugliano D. A journey into a Mediterranean diet and type 2 diabetes: A systematic review with meta-analyses. BMJ Open. 2015; 5(8).

- 39.Ajala O, English P, Pinkney J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of different dietary approaches to the management of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013; 97.

- 40.Estruch R, Martínez-González MÁ, Corella D, Salas-Salvadó J, Ruiz-Gutiérrez V, Covas MI, et al. Effects of a Mediterranean-Style Diet on Cardiovascular Risk Factors. Ann Intern Med. 2006 July; 145(1).

- 41.Santangelo C, Filesi C, Varì R, Scazzocchio B, Filardi T, Fogliano V, et al. Consumption of extra-virgin olive oil rich in phenolic compounds improves metabolic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a possible involvement of reduced levels of circulating visfatin. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation volume. 2016; 39.

- 42.Bock Md, Derraik JG, Brennan CM, Biggs JB, Morgan PE, Hodgkinson SC, et al. Olive (Olea europaea L.) Leaf Polyphenols Improve Insulin Sensitivity in Middle-Aged Overweight Men: A Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Trial. PLoS One. 2013 March; 8(3).

- 43.Boucher JL. Mediterranean Eating Pattern. Diabetes Spectrum. 2017 May; 30(2).

- 44.Harvard University. Diet Review: Mediterranean Diet. [Online]; 2018 [cited 2023 March 15] Available from: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/healthy-weight/diet-reviews/mediterranean-diet/

- 45.CDC. Improving Your Eating Habits. [Online]; 2022 [cited 2023 March 20] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/losing_weight/eating_habits.html

- 46.Helland MH, Nordbotten GL. Dietary Changes, Motivators, and Barriers Affecting Diet and Physical Activity among Overweight and Obese: A Mixed Methods Approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 October; 18(20).

- 47.U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. [Online]; 2020 [cited 2023 March 17] Available from: http://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/

- 48.NHS. The Eatwell Guide. [Online]; 2022 [cited 2023 March 17] Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/food-guidelines-and-food-labels/the-eatwell-guide/#:~:text=On%20average%2C%20women%20should%20have,including%20how%20active%20you%20are.

- 49.World Health Organization. Healthy diet. [Online]; 2020 [cited 2023 March 17] Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/healthy-diet

- 50.Ministry of Health. Eating and Activity Guidelines for New Zealand Adults. [Online]; 2015 [cited 2023 March 17] Available from: https://www.ptdirect.com/training-design/nutrition/national-nutrition-guidelines-new-zealand/at_download/file

- 51.National Health and Medical Research Council. Australian Dietary Guidelines. [Online].; 2013 [cited 2023 March 17. Available from:https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/australian-dietary-guidelines.pdf

- 52.Brown MD, Lackey HD, Miller TK, Priest D. Controlling Calories—The Simple Approach. Diabetes Spectr. 2001; 14(2).

- 53.Harvard University. Healthy Eating Plate. [Online]; 2011 [cited 2023 March 17] Available from: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/healthy-eating-plate/

- 54.Chester B, Babu JR, Greene MW, Geetha T. The effects of popular diets on type 2 diabetes management. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2019.

- 55.Dora R, Teresa N, Anne-Claire V, Traci M, M MA, Antonio A, et al. Mediterranean dietary patterns and prospective weight change in participants of the EPIC-PANACEA project. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2010 October ; 90(4).

56.Babio N, Bulló M, Basora J, Martínez-González M, Fernández-Ballart J, Márquez-Sandoval F, et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet and risk of metabolic syndrome and its components. Nutrition, Metabolism & Cardiovascular Disease. 2008. - 57.Kesse-Guyot E, Ahluwalia N, Lassale C, Hercberg S, Fezeu L, Lairon D. Adherence to Mediterranean diet reduces the risk of metabolic syndrome: A 6-year prospective study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2013 July; 23(7).

- 58.K. Esposito MR, M C, C DP, F G, G G, M D, et al. Effect of Mediterranean-style diet on endothelial dysfunction and markers of vascular inflammation in the metabolic syndrome: a randomized trial. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2004; 289.

- 59.Paula J, Antonio B, José TM, José SM, et al. Adherence to a Mediterranean Diet Is Associated with Reduced 3-Year Incidence of Obesity. Journal of Nutrition. 2006 November; 136(11).

- 60.Serra Majem L. Efficacy of diets in weight loss regimens: is the Mediterranean diet appropiate? Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2008; 118(12).

- 61.Locke A, Schneiderhan J, Zick SM. Diets for Health: Goals and Guidelines. Am Fam Physician. 2018; 97(11).

- 62.Medina-Remón A, Tresserra-Rimbau A, Pons A, Tur JA, Martorell M, Ros E, et al. Effects of total dietary polyphenols on plasma nitric oxide and blood pressure in a high cardiovascular risk cohort. The PREDIMED randomized trial. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015 January; 25(1).

- 63.Morze J, Danielewicz A, Przybyłowicz K, Zeng H, Hoffmann G, Schwingshackl L. An updated systematic review and meta-analysis on adherence to mediterranean diet and risk of cancer. European Journal of Nutrition. 2021; 60.

- 64.Schwingshackl L, Hoffmann G. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Medicine. 2015 October ; 4(12).

- 65.Schwingshackl L, Schwedhelm C, Galbete C, Hoffmann G. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet and Risk of Cancer: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2017 September ; 9(10).

- 66.Valls-Pedret C, Sala-Vila A, Serra-Mir M, Corella D, Torre Rdl, Martínez-González MÁ, et al. Mediterranean Diet and Age-Related Cognitive Decline: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 July; 175(7).

Kindly Let Us Know If This Was helpful? Thank You!